The main focus of my visit to Bhutan was to walk the Snowman Trek. As the result, I did not have the time nor the opportunity to explore the rich cultural heritage of this beautiful country in depth it deserves. The hike up to the Tiger Nest Monastery was really part of the Snowman (although not on the Snowman trail proper). The variety and depth of the Bhutanese culture warrant a separate trip dedicated to exploring its heritage.

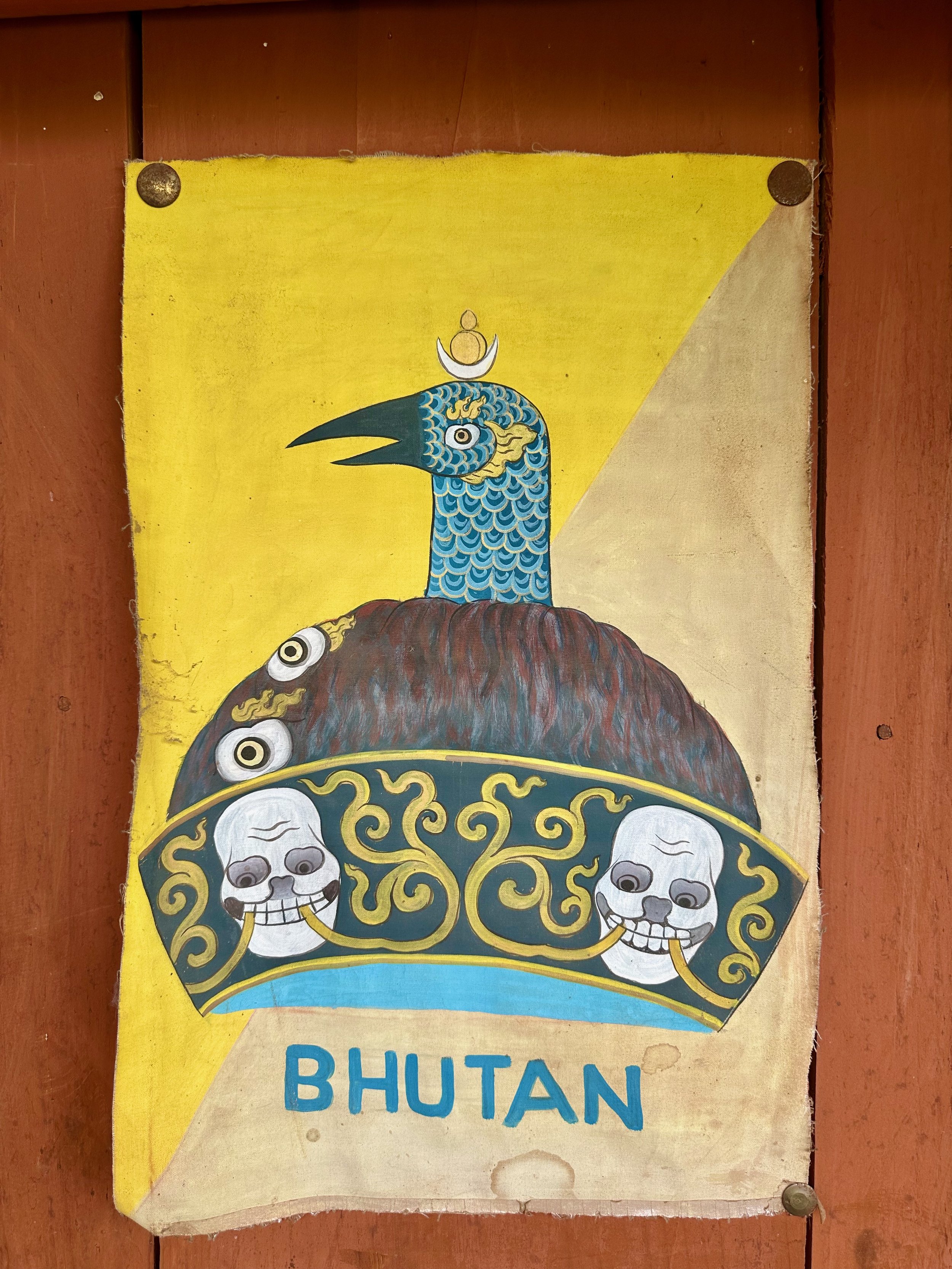

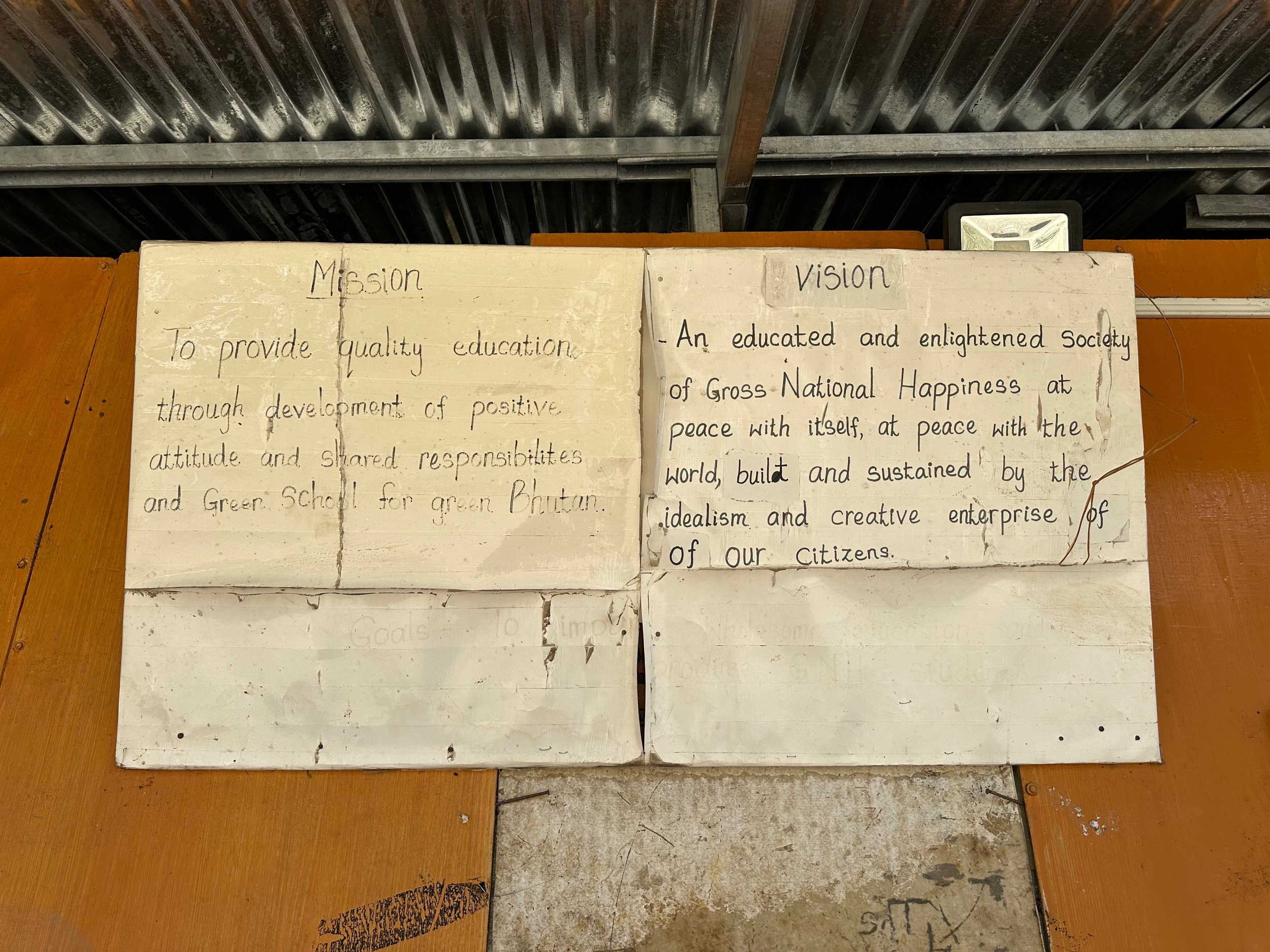

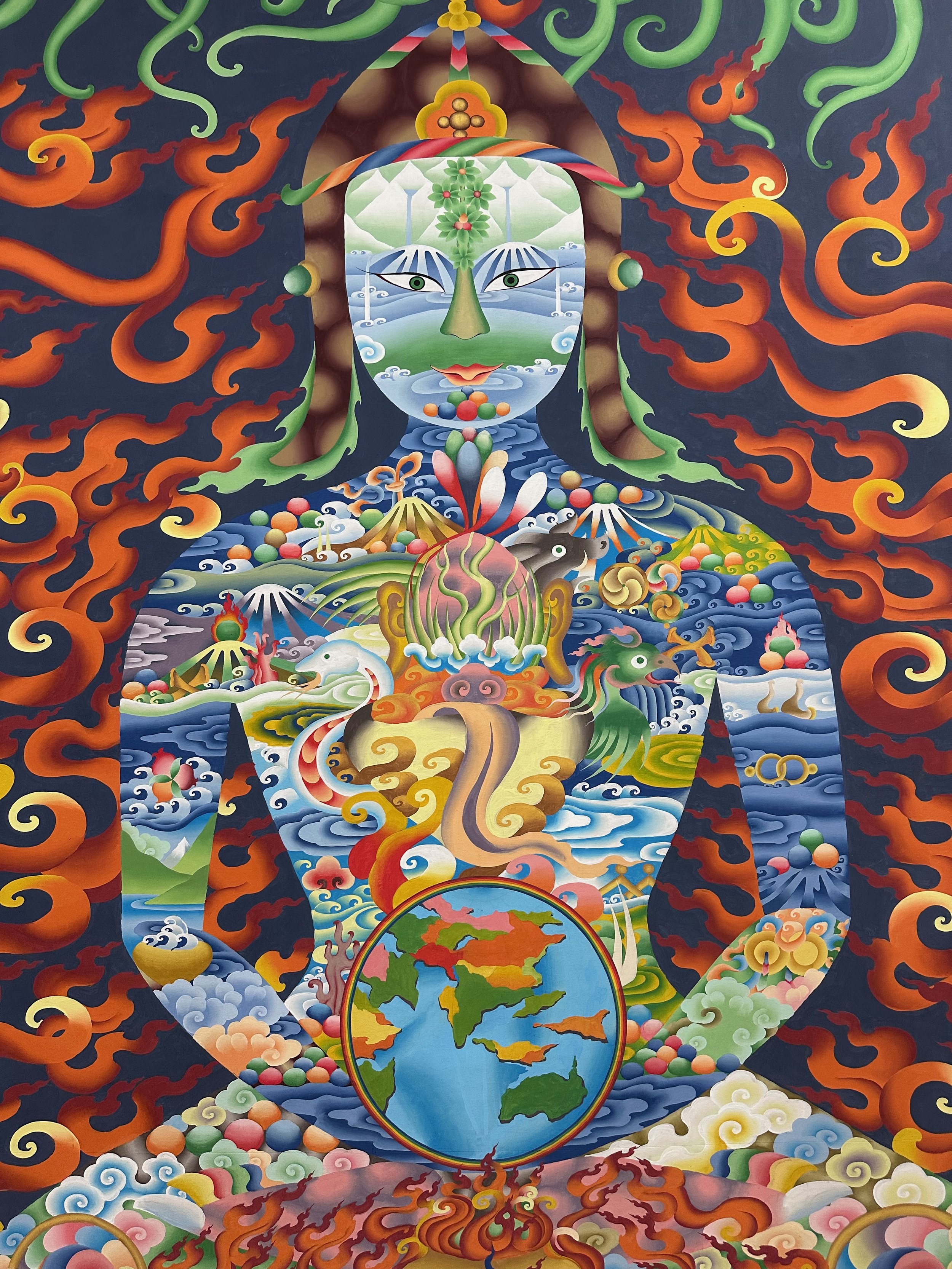

Culturally, Bhutan is like no other Himalayan country. It is unique with its customs, dress and folklore. Its architecture is distinct and at times, monumental in scale. Even the Buddhist traditions are different from Nepal or India. One cannot ignore the visual impact of the Divine Madman and his Thunderbolt of Wisdom. Bhutan’s art is different from Nepal and India. Even the Tanka paintings are different. Bhutan employs ample resources to maintain its Gross Domestic Happiness index, the culture being one of the four of its pillars.

My overall impression was, that Bhutan resembles Switzerland of the Himalaya but less focused on money and banking and more on Buddhism, its king and overall equality for all Bhutanese. Of course it is a very superficial impression based on my very brief exposure to the actual Bhutanese society (and not its beautiful mountains).

Here is the snapshot of the sights I managed to visit on the way to and from the Snowman Trek.

The image of the Royal Family greets you at the arrival at Paro airport.

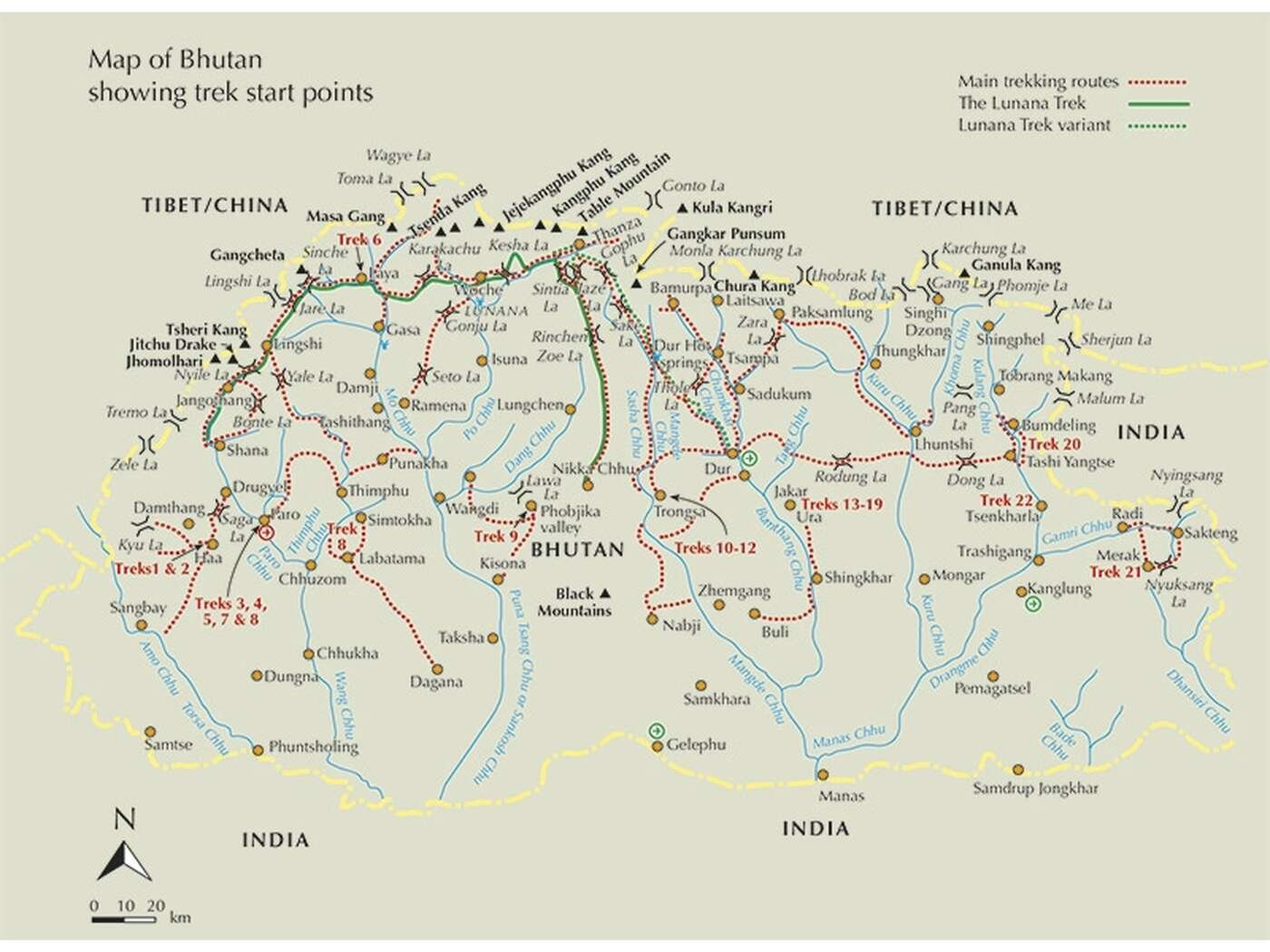

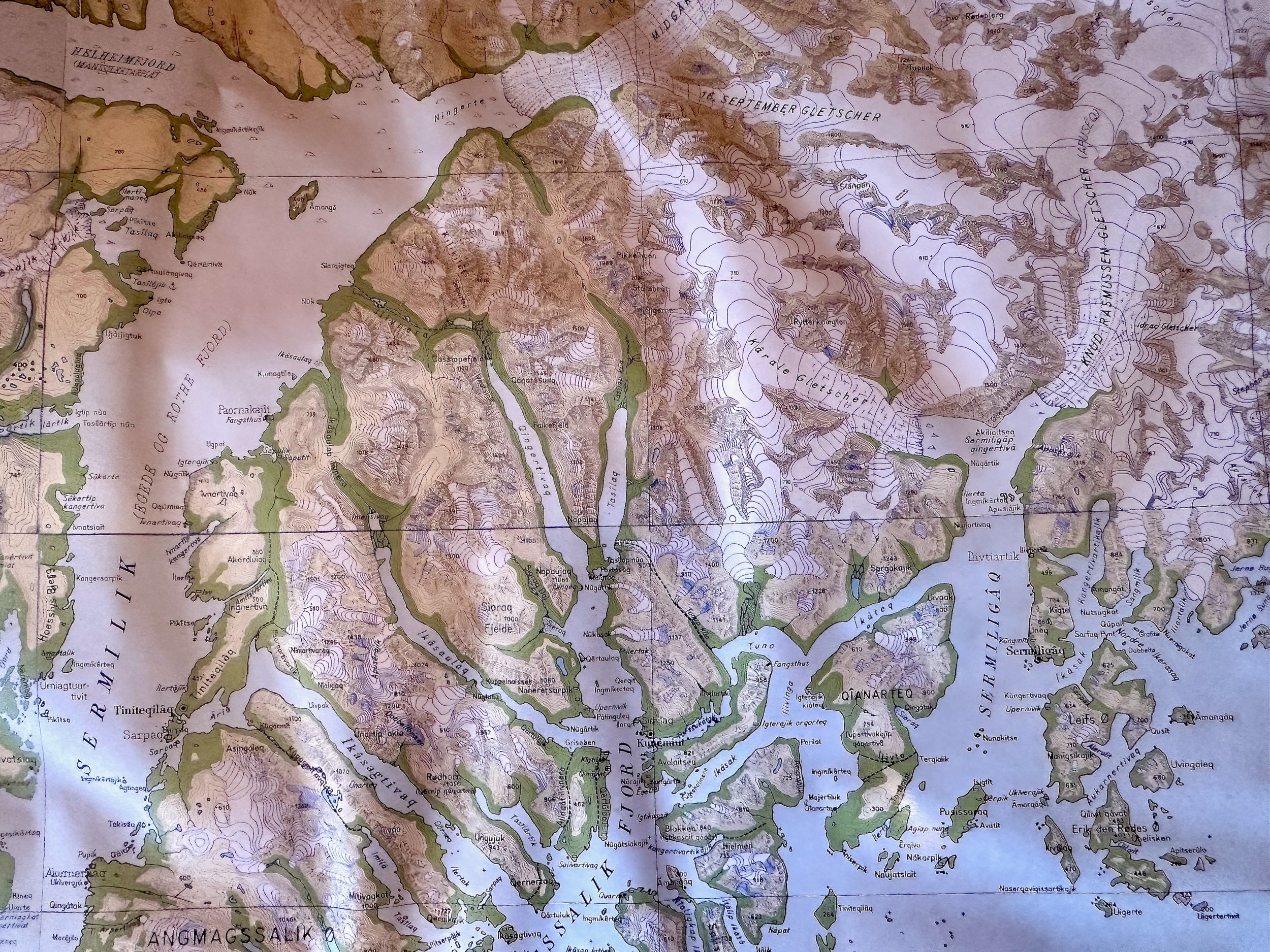

Where is Bhutan? It is a common question.

The Snowman Trek covers the top north - western quarter of the country. There is much more to explore!

The attractive people of the Royal Family wearing the finest of the traditional dress.

The King cult is present even in the remotest of villages.

Paro Town and Paro Valley

Paro Valley

Paro Valley

Sitting precariously 800 metres above the Paro valley, the Paro Taktsang Monastery (Tiger’s Nest Monastery) was built in the late 17th century on the site of a cave set into the cliff. Taktsang more accurately translates to “tigress’ lair” and aptly gets its name from the legend of its founding.

According to that legend, the 8th-century Indian Buddhist master Guru Rinpoche was carried up the mountain on the back of a disciple who had transformed herself into a tigress. Once they arrived, Guru Rinpoche then spent 3 years, 3 months, 3 days and 3 hours meditating in the cave. After he had finished, it became a holy place and became known as Paro Taktsang.

The monastery complex was built in 1692 by 4th Druk Desi Tenzin Rabgey around the Taktsang Senge Samdup cave, where Guru Padmasambhava meditated and practiced with students including Yeshe Tsogyal before departing the Kingdom of Tibet in the early 9th century.

A small temple where Yeshe Tsogyal meditated for 3 years, 3 months and 3 hours.

Taktsang Monastery (Tiger’s Nest)

Taktsang Monastery (Tiger’s Nest)

Taktsang Monastery (Tiger’s Nest) and the lush Paro Valley.

Beautiful temple in the Taktsang Monastery

Taktsang Monastery

Taktsang Monastery

There were too many accidents with butter lamps in the past. It seems that all places of worship that we visited were at some point burned down by fire started by a butter lamp. Now the butter lamps are housed in a separate enclosed building were the monks can play with them with no fear of burning down the house.

To help you get to the Tiger’s Nest, you can rent a walking stick or hire a decked out mule for no effort on your part experience. The easy walkup to the monastery complex takes 45min on a highway of a trail.

Bhutanese Magpie

Paro Dzong. Paro Dzong, officially called Rinpung Dzong, was constructed in 1646 under the guidance of Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyel, the unifier of Bhutan. It was strategically built on a hill overlooking the Paro Valley to serve as both a fortress and a monastery. The site was chosen for its defensive advantages, protecting the region from Tibetan invasions.

Beyond its role in military defense, Paro Dzong has long been a central figure in the Bhutanese administration and religion. The Dzong has housed the district's government offices and monastic quarters, representing the delicate balance between Bhutan's civil and spiritual leadership. It played a crucial role in safeguarding the country's sovereignty during conflict and is a living symbol of Bhutan's rich heritage.

Paro Dzong is a masterpiece of traditional Bhutanese architecture, showcasing the country’s unique building techniques. The fortress is adorned with intricate wood carvings, bright murals, and exquisite paintings that narrate Buddhist legends. Its five-story central tower (Utse) stands tall, offering a glimpse into Bhutan's ancient architectural prowess.

The Dzong played a very important role in the history of the country as it served as a very effective stronghold to repel repeated Tibetan invasions during the 17th and the 18thcentury. Though it did suffer damages due to the earthquake in 1897 and fire in 1907, it was restored to its former glory in due course of time. Formerly it served as the Meeting Hall for the National Assembly but today it houses the Monastic Body and the District Government offices.

Paro Dzong

Paro Dzong

Paro Dzong

Prayer Hall in Paro Dzong

Paro Dzong

Paro Dzong

The Punakha Dzong (the palace of great happiness or bliss), is the administrative centre of Punakha District in Punakha, Bhutan. The dzong was constructed by Ngawang Namgyal, in 1637–38. It is the second oldest and second largest dzong in Bhutan and one of its most majestic structures. The dzong houses the sacred relics of the southern Drukpa Lineage of the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, including the Rangjung Kasarpani and the sacred remains of Ngawang Namgyal and the tertoen Pema Lingpa.

The Dzong is located at the confluence of the Pho Chhu (father) and Mo Chhu (mother) rivers in the Punakha–Wangdue valley. The source of the Mo chu river is in the northern hills of Ligshi and Laya in Bhutan, and in Tibet. The Pho Chu River is fed by glaciers in the Lunana region of the Punakha valley. After the confluence of these two rivers, the main river is known as Puna Tsang chu.

The wooden bridge to Phunaka Dzong

Phunaka Dzong

Phunaka Dzong main prayer hall

Paro

Paro

In the region, there is a custom to chew areca nut and betel leaf because of its breath-freshening and relaxant properties. Sometimes there is a sexual symbolism attached to the chewing of the nut and the leaf. The areca nut represented the male and the betel leaf the female principle. Regular doma chewing causes the lips and tongue to be stained red.

Archery - the national sport of Bhutan

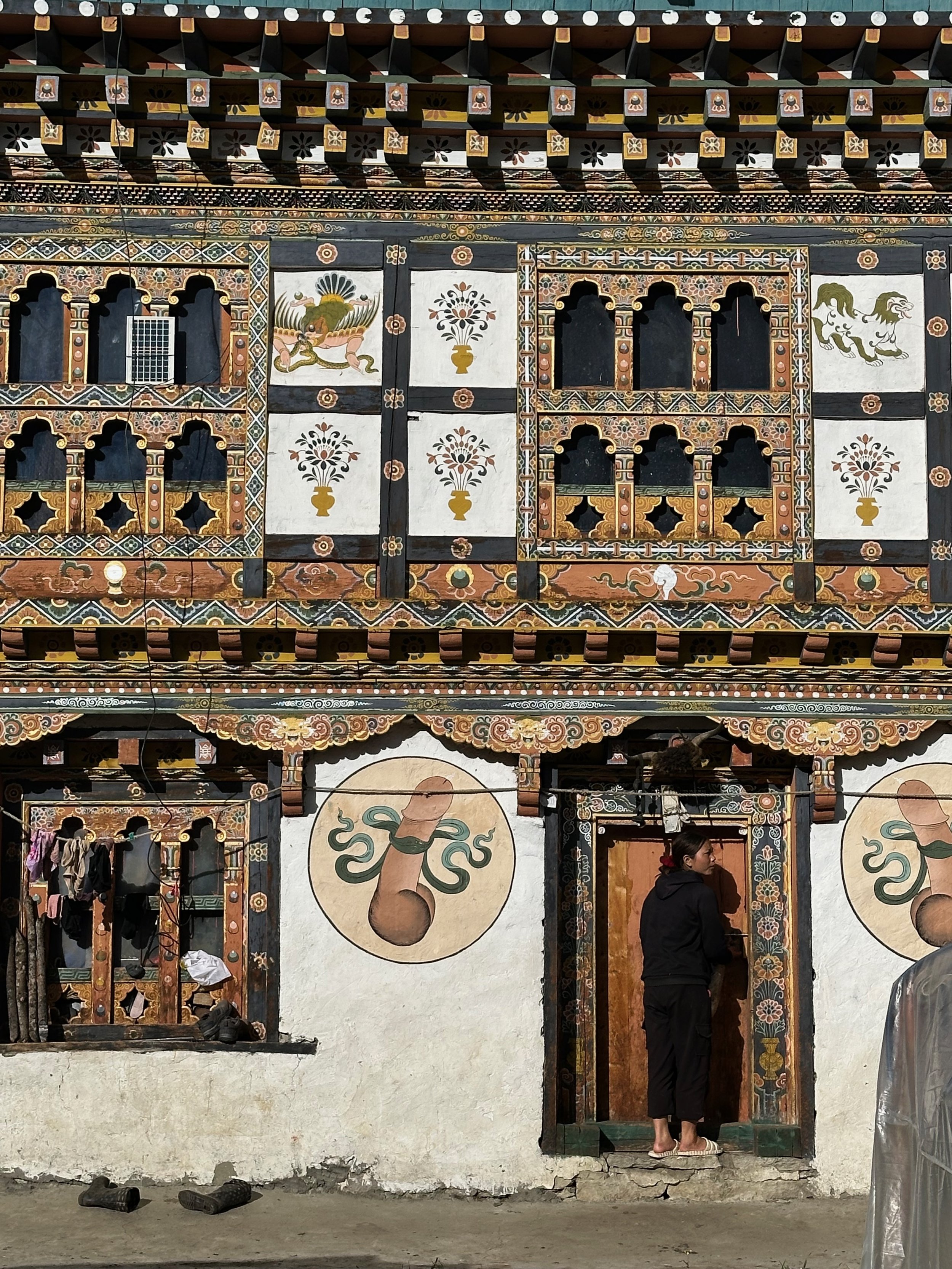

Phallus paintings in Bhutan are esoteric symbols, which have their origins in the Chimi Lhakhang monastery near Punakha, the former capital of Bhutan. The village monastery was built in honour of Lama Drukpa Kunley who lived at the turn of the 16th century and who was popularly known as the "Mad Saint" (nyönpa) or “Divine Madman” for his unorthodox ways of teaching, which amounted to being bizarre and shocking. He was a crazy saint who extensively travelled in Bhutan, who was fond of women and wine, and adopted blasphemous and unorthodox ways of teaching Buddhism. His sexual exploits included his hosts and promoters. He was utterly devoid of all social conventions and called himself the "Madman from Kyishodruk. Drukpa Kunley's intention was to shock the clergy, who were uppity and prudish in their behaviour and teachings of Buddhism. However, his ways appealed to lay practitioners. It was he who propagated the legend of painting phalluses on walls and flying hanging phalluses from roof tops of houses to drive away evil spirits and subdue demonesses.

The explicit paintings have become embarrassing to many of the country's urbanites, and this form of folk culture is informally discouraged in urban centers as modern Abrahamic cultural norms of shaming the human body and sexuality have spread in Bhutan's urban centers.

However phallus paintings can still be seen on the walls of houses and buildings throughout Bhutan, particularly in villages, and are credited as Kunley's creations. Traditionally symbols of an erect penis in Bhutan have been intended to drive away the evil eye and malicious gossip. The phallic symbols are generally not depicted in community temples and dzongs, which are places of worship where lamas or Buddhist monks and nuns who have adopted celibate lifestyles live. However, rural and ordinary houses continue to display them. Kunley's organ, as painted, is called the "Thunderbolt of Flaming Wisdom" as it unnerved demons and demonesses and subdued them. It is also said that he is "perhaps the only saint in the religions of the world who is almost exclusively identified with phallus and its creative power". It is for this reason that his phallus, as a symbol, is depicted in paintings on the walls of the houses.

While the history of use of phallus symbols is generally traced to Drukpa Kunley, studies carried out at the Center of Bhutan Studies (CBS) have inferred that the phallus was an integral part of the early ethnic religion associated with Bon that existed in Bhutan before Buddhism became the state religion. In Bon, the phallus was integral to all rituals. It is also argued by social science researchers that the phallus is a representation of "Worldly illusion of desires", and it is said that as a symbol of power and fertility of the animists of the Bön religion, the phallus's representation got enmeshed with Buddhism in Bhutan.

The belief that such a symbol brings good luck and drives away evil spirits is so much ingrained in the psyche of the common populace in Bhutan that the symbols are routinely painted outside walls of the new houses and even painted on number plates of trucks. The carved wooden phalluses are hung (sometimes crossed by a design of sword or dagger) outside, on the eaves of the new homes, at the four corners. As part of house warming ceremony of new houses, a traditional ritual involves erecting the phallus symbols at the four corners of the eaves of the house and one inside the house. A basket filled with carved wooden phalluses is raised to the roof of the house to fix them at the four cardinal corners. Groups of both men and women get hired by the owner of the house in raising the basket to the roof. (Credit to WIKIPIDIA for the wealth of info on this topic).

Thimpu - the capital of Bhutan

Why are all roofs green you ask? “All buildings in Thimphu city have been ordered to paint their roofs red and green by the end of the year or pay a hefty fine. The decision, according to the Thromde, is for the city’s aesthetics and for environmental reasons. Meanwhile, this arrangement has not gone well with the residents.

The Thromde has given till the end of December to complete the roof paintings.

All residential and commercial buildings in the city will need to have their roofs painted green, while government and institutional buildings should have red roofs.

Failure to do so will be penalized with a fine of Nu 50,000, the Thromde stated through a notification on 10th August.”

Thimpu

The gho is a traditional garment worn by Bhutanese laymen. It consists of three to four lengths of cloth that are sewn together to form a floor-length, left-crossing, loose robe with long sleeves. The robe overlaps in front, folds into two wide pleats at the back, and is held in place with a belt; it is then drawn up to achieve the desired length. The lengths of cloth are vertical; the gho is generally woven in silk or cotton in a variety of patterns.

The women in Bhutan dress elegantly in an ankle-length dress known as Kira. They are firmly fastened at the shoulders with either simple pins or complicated silver brooches also known as Koma. This is one way of wearing it. The other way is to wear it like a skirt down the waist, we refer to it as half Kira.

Traditionally they were handwoven with intricated designs and patterns made of raw silk. Nowadays they can be machine-made with cotton and other fibres. On special occasions, women wear bright coloured, complex-designed Kiras whereas, on ordinary days, they wear light weighted and simple patterned Kiras. Keeping in line with fashion, women in Bhutan these days match their Kiras with accessories, blouses, and even footwear.

One of the distinctive features of the women of Laya is their bamboo hat worn that is with colourful beads. The hat hardly covers the head. It neither protects them from rain or the sun but for the young women of Laya today, the hat is among the ornaments they save to wear during festivals.

The hat was worn daily a decade ago but not anymore. Today, are only two persons, a man and a woman in Laya’s Neylu chiwog who can weave the bamboo hat. Laya has five chiwogs with a population of more than 12,000 people.

Dorji is 52 years and Chimi Dem is 47.

Dorji said that the younger ones are not interested to learn hat weaving. “It’s concerning to see the hat disappearing. I am worried that it might die with me. No one is interested to learn,” he said. Dorji said that the elderly women who wear the hat daily are his regular buyers. “The hat hardly lasts a year.”

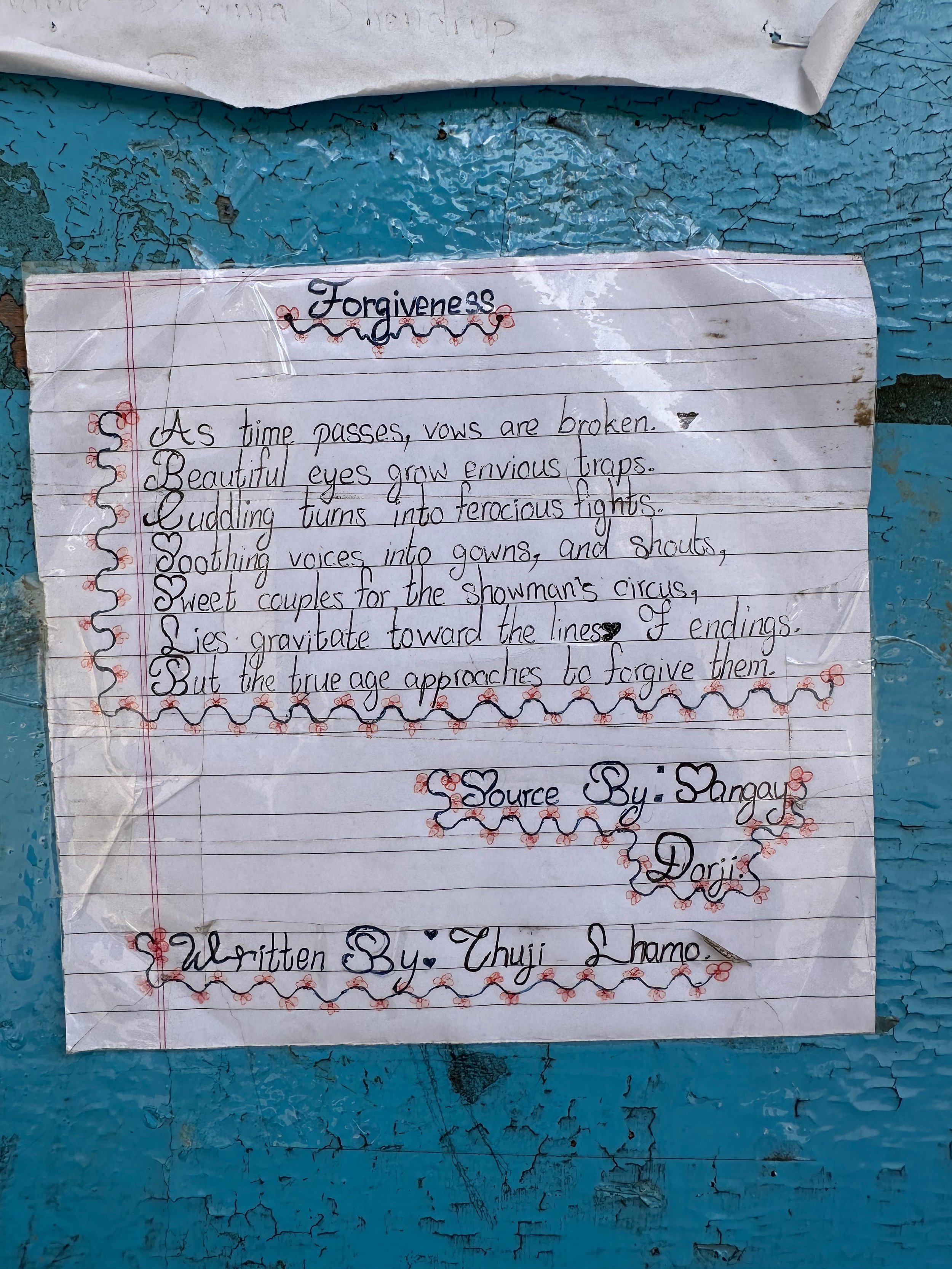

Relaxing in Laya

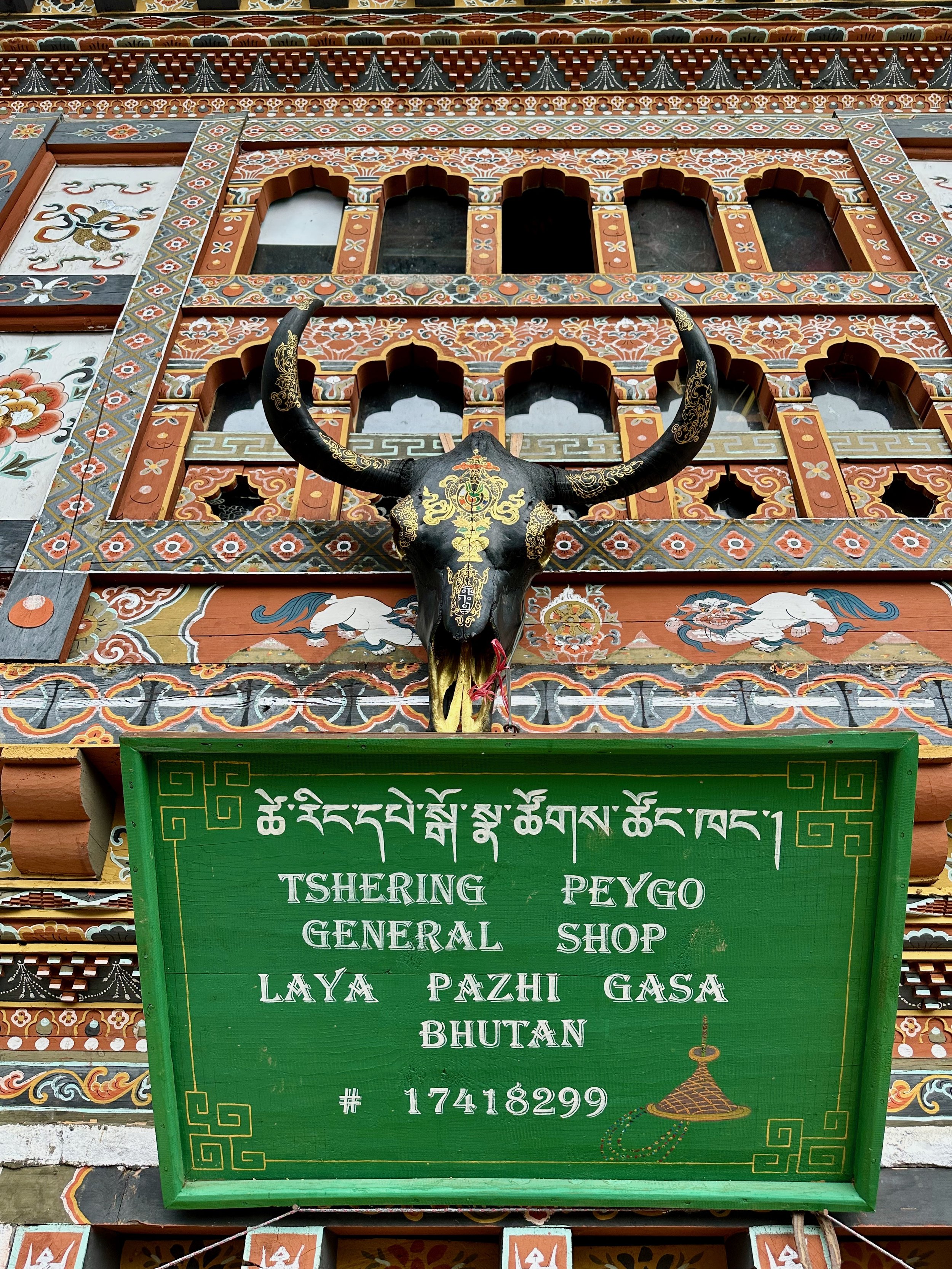

Laya

Laya

Laya Home

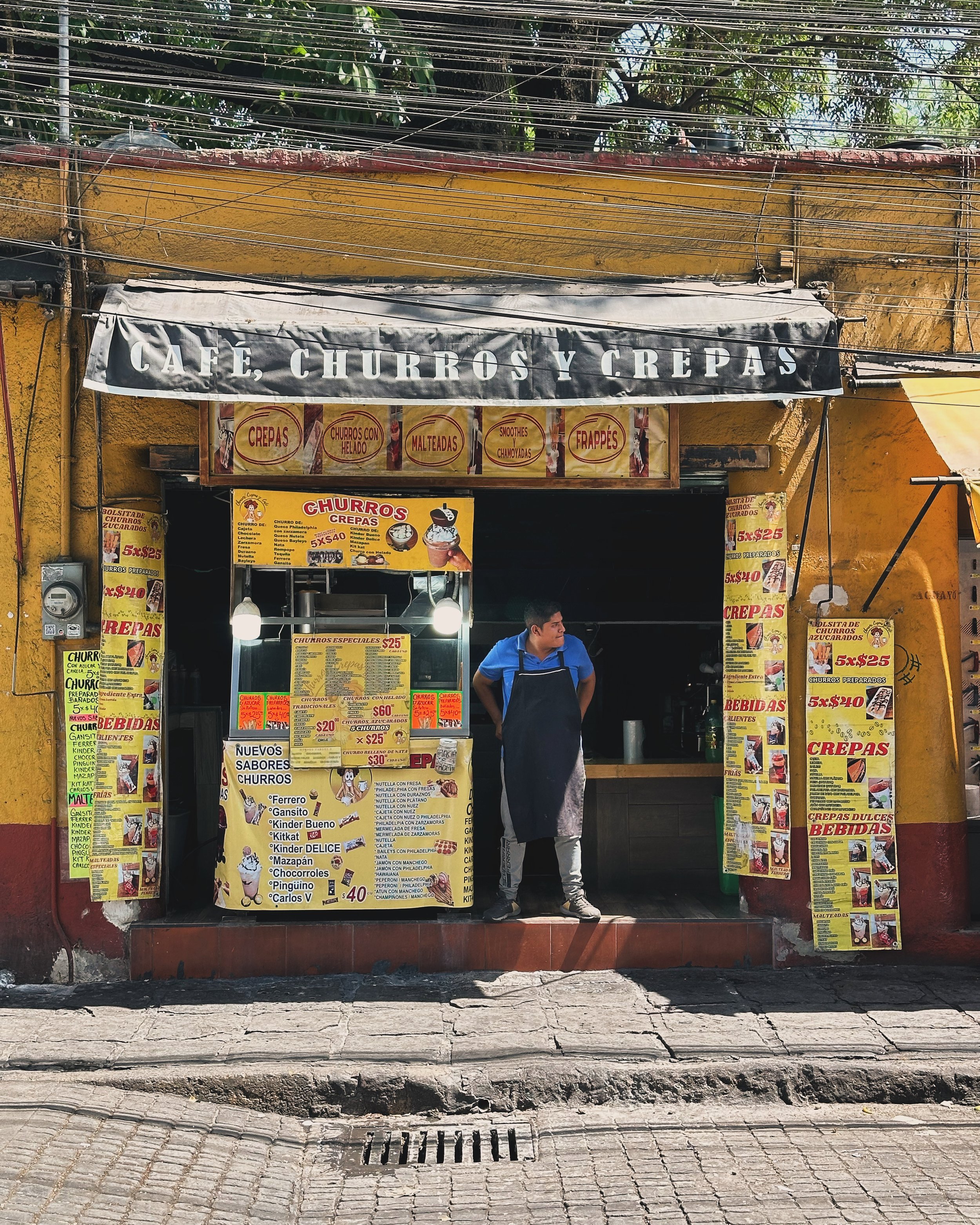

Laya Bar and hangout

A small temple in Laya