Ephesus, the old port of the Romans

Mt. Kailash, Simikot to Kailash in Tibet Photos

The 6,714m high Mt. Kailash raises above the Plane of Burang and has is the world's most holy place at the same time that it is the least visited. Hindus believe Mt.Kailash to be the abode of Lord Shiva. The Jains call the mountain Astapada and believe it to be the place where Rishaba, the first of the twenty-four Tirthankaras attained liberation. Followers of Bon, Tibet's pre-Buddhist, shamanistic religion, call the mountain Tise and believe it to be the seat of the Sky Goddess Sipaimen. The Buddha is believed to have magically visited Kailash in the 5th century BC. Tibetan Buddhists call the mountain Kang Rimpoche, the 'Precious One of Glacial Snow', and regard it as the dwelling place of Demchog and his consort, Dorje Phagmo. Three hills rising near Kang Rimpoche are believed to be the homes of the the Bodhisatvas Manjushri, Vajrapani, and Avalokiteshvara.

Mt. Kailash, the mountains in the border of Nepal/India/China and Gurla Mandata

Lake Manasarovar and Mt. Gurla Mandata

Swayambhunath or "The Monkey Temple" in Kathmandu

Human skull at the Kathmandu market

Swayambhunath or The Monkey Temple in Kathmandu

Kathmandu

Swayambhunath or The Monkey Temple in Kathmandu

In the Tibetan part of Kathmandu

Swayambhunath or The Monkey Temple in Kathmandu

Nepalganj

Flying to Simikot

Simikot dirt airstrip

Simikot

The start of the trail to China from Simikot

Western Nepal - a village close to Simikot

The distinct look of people from Western Nepal

Salt traders - little goats carry bags with salt from Tibet

The traders use horses and mules for their trade with Tibet

Navigating steep trails can be difficult for the mules

Hospitality along the trail

Smoking a traditional pipe

Smoking something stronger than the traditional pipe

Goat herder

At the military checkpost - we are approaching the border area close to China

Dinner time - it was very wet and cold. We were all very appreciative of little heat.

We had wet and cold conditions. Also muddy!

The approach to the Nara La Pass, the mud and rain turned into snow and ice.

Top of the pass - wideout and blowing wind

Nara La Pass 4,507m - the last pass in Nepal. The traders use Yaks to transport goods from Tibet to Nepal

Nara La Pass 4,507m and the caravan of yaks returning from Tibet.

We arrived in Hilsa cold and wet.

Descent from Nara La Pass 4,507m to Hilsa, the border outpost in Nepal

Hilsa and the bridge to China

Bridge to China

Local porters lining up for work with Indian pilgrims.

Tibetan roads back then. The road from Hilsa to Burang.

The Himalayas on the border of Nepal, India and China

An old stupa and the Himalayas on the border with Nepal, India and China

Dhaulagari 6,838m in Western Nepal on the border of Nepal, China and India

Jokopahar 6,744m in Western Nepal on the broder of Nepal, Tibet and India

The Chinese outpost of Burang

Gurla Mandata

Lake Rakshastal at 4,590m which is connected to Lake Manasarovar

Lake Rakshastal at 4,590m which is connected to Lake Manasarovar

Lake Manasarovar at 4,590m. According to the Hindus, the lake was first created in the mind of the Lord Brahma after which he manifested on Earth.

Lake Manasarovar. The Buddhists beleive that this is where the Lord Buddha was conceived. The lake has a few monasteries on its shores, the most famous is the ancient Chiu Gompa built on a steep hill overlooking the lake. Swimming in the lake is supposed to wash away all the sins. Many Indian pilgrims come to this lake to swim.

Lake Manasarovar and the barren hills of Tibet

Lake Manasarovar

The stupas and a lone guesthouse on the hills overlooking Lake Manasarovar

Chiu Gompa built in the 8th century.

Chiu Gompa

Chiu Gompa - the main gate

Chiu Pompa

Prayer flags above the Chiu Gompa.

The solitary monk at the Chiu Gompa who showed us around.

Inside the Chiu Gompa

The view from Chiu Gompa. Mt Kailash was in the clouds.

The view of the Lake Mansowar from Chiu Gompa

The stupas overlooking Lake Manasarovar. The stones have inscriptions of Buddhist prayers (they are called Mani Stones). The yak horns are also carved with prayer inscriptions (Om Mani Padme Hum).

Mani stones on the shore of Lake Marasoravar

Prayer wheels

An old prayer wheel powered by wind blades. The silence is broken by the sound of the wind and the squeaks of the wind-powered prayer wheel. For one of the holiest places on Earth it had a very remote and secluded feel.

The symbol of Tibetan Buddhism. Emptiness and the wind.

Endless horizons

The endless horizon of Western Tibet - a very special place - Nanda Devi is very close. It is another holy mountain located on the Indian side of the range.

Our camp at Lake Mansowar

Gurla Mandata

Darchen

Darchen and our hotel.

The ceremonial area of Mt. Kailash.

Mt. Kailash. A place where the sky burial ceremonies are performed. A sky burial is a dismemberment of a dead body with knifes and feeding it to the vultures. In this part of Tibet, there is no wood to burn the dead.

Mt. Kailash on the right. The beginning of the outer Kora.

One of a few monasteries dotting Mt. Kailash.

Mount Kailash, the western flank.

Mt. Kailash - western flank. It has these unreal rock formations.

The yaks carrying supplies to the monastery at the back side (north) of Mt. Kailash.

A tea house on the Kora of Mt. Kailash.

Om Mani Padme Hum - approaching the north side of Mt. Kailash

The Dirapuk Monastery at the north side of Mt. Kailash.

Mount Kailash north side

At the Dirapuk monastery at the north side of Mount Kailash at 5,080m.

At the Dirapuk Monastery, a typical western Tibetan attire and facial features of the Tibetan Khampa (nomad).

Young monks at the Dirapuk Monastery

North/North east side of Mount Kailash at sunrise

Mt. Kailash - north east face

The north face of Mt. Kailash

Last view of Mt. Kailash from the north

Along the Kora of Mt. Kailash

Mt Kailash in the distance

At the Lake Mansowar

Roads in western Tbet back then...We had many flat tires.

Gurla Mandata

The North face of Mt. Kailash

The plane of Burang and the Gurla Mandata massif

A Tibetan monk on the Mt. Kailash kora

A Tibetan monk/pilgrim approaching the Dolma La Pass at 5,648m

Tibetan pilgrims on the kora of Mt. Kailash

The view of the Langtang Range from Tibet near Lake Paiku Tso

Old Tingri close to Cho Oyu

Tibet

Burang, Tibet

Burang, Tibet

Darchen, Tibet. Mt. Kailash in the distance.

Darchen, Tibet

Darchen, Tibet. Gurla Mandata is in the distance.

Lake Mansowar and Gurla Mandata

Pit stop by Lake Mansowar.

Close to Mt. Kailash on the Plane of Burang.

Plane of Burang and Girl Mandata

In Western Tibet

Western Tibet

The Langtang Range from the Tibetan side. The large mountain on the left is Gang Beng Chen 7,281m

Pilgrims on the way to Mt. Kailash

Near Tingri

Everest Basecamp area in Tibet

Mt. Everest

The Chinese side of Everest

Old mediation caves close to Everest

Old meditation cave close to the Rongbuk Monastery

Rongbuk Monastery on the north side of Mt. Everest

Rongbuk Monastery

Rongbuk Monastery close to North side of Everest

North of Shishapangma

Mt. Everest from Tibet

Approaching the Langtang Range

Gang Beng Chen 7281m and the Tibetan Plateau

Somewhere north of the Nepal Mustang

The Himalaya Range from the Tibetan Plateau. The mountains on the horizon are the Domodar Himal close to Mustang in Nepal.

The Dolpo Himalaya seen from Tibet

The Himalaya from Tibet

Gurla Mandata and Lake Manasovar

Gurla Mandata

Mt. Kailash and the Plain of Burang

The Pass between Nepal and Tibet along the Friendship Highway

Mt. Kailash

Mt. Kailash

Lake Mansovar

Lake Mansovar

Gurla Mandata

On the way to north side of Everest

Close to Cho Oyu

The Langtang Range from Tibet

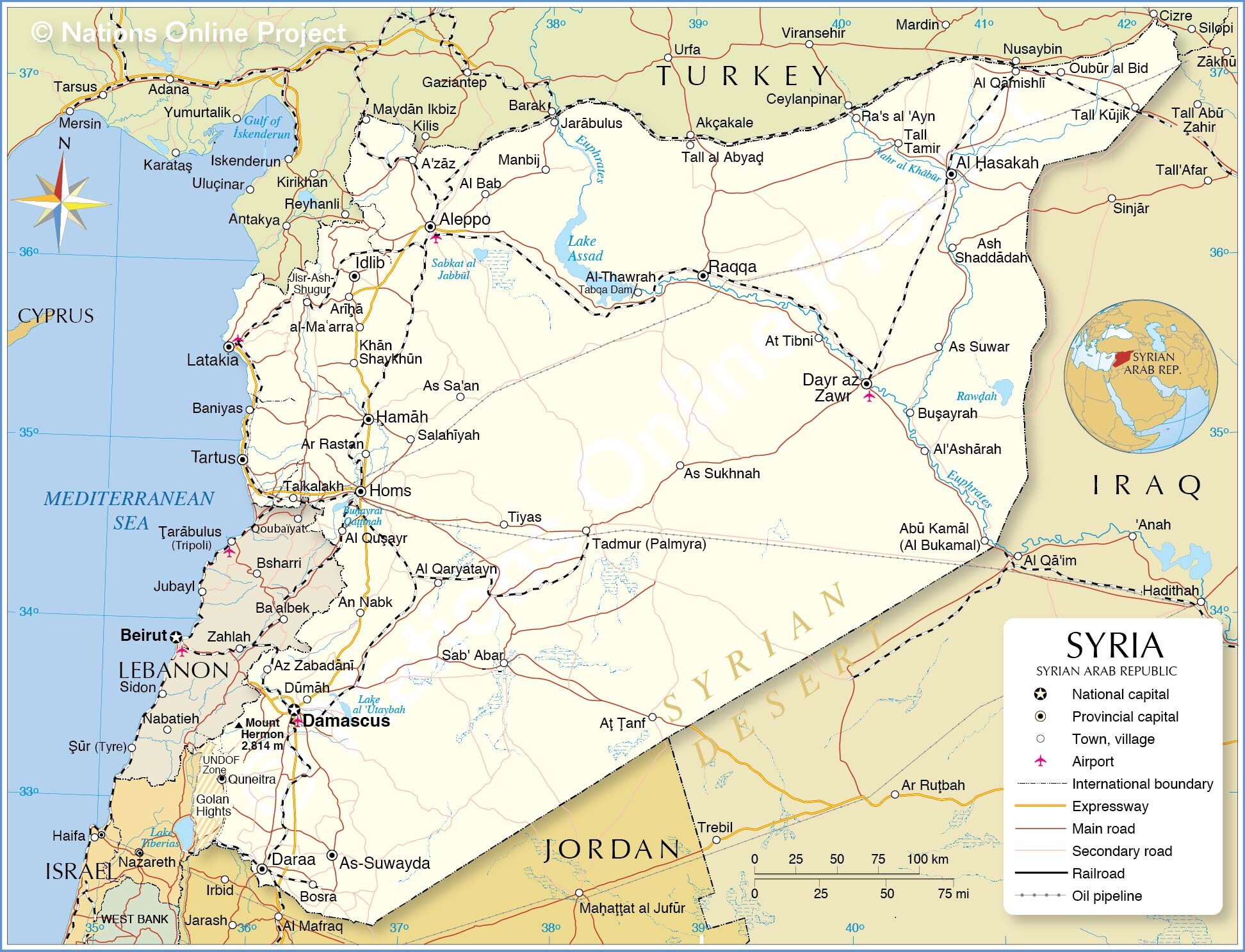

Syria

Umayyad Mosque in Damascus

Umayyad Mosque in Damascus

Umayyad Mosque in Dmascus

The Souq of Damascus

Umayyad Mosque

Umayyad Mosque

The place where the head of John the Baptist is held, inside the Umayyad Mosque. Built in the year 706 on the site of early Christian temple dedicated to John the Baptist.

Umayyad Mosque

Umayyad Mosque

The souq of Damascus

Damascus

Palmyra - the ancient Silk Road city

Palmyra

The citadel of Palmyra

The Temple of Bel built in 32 AD

The Temple of Bel

The Temple of Bel built in 32 AD and destroyed in 2015

Arch of Triumph destroyed in 2015

Palmyra Theatre destroyed in 2015

The Baths of Diocletian

Valley of Tombs

Crusader's castle Crack de Chavalier

Some of the oldest Christian churches in the world are in Syria. Some were built during the times of the apostles.

The ancient Roman city of Bosra

The Roman theatre built in year 150 AD

The ancient Roman City of Apamea established in 300 BC.

Roman city of Apamea

The great colonnade built in 300BC.

Aleppo

The Aleppo Citadel

Aleppo

The Great Mosque of Aleppo built in the year 717. The minaret was built in the year 1090. It was destroyed recently.

The souq of Aleppo.

The souq of Aleppo.

Inside one of the old Roman houses.

India - North

New Delhi

New Nehli - Old Fort

Old Fort of New Delhi

Personal space - non existent at the New Delhi fort

New Delhi

New Delhi

New Dehli

New Dehli

New Delhi

New Delhi main railway station - a fascinating cross road of Indian cultures and people

New Delhi

The stylist and his assistant

Dr Vimla to the rescue!

New Delhi

Back streets of Old New Delhi

Shave time!

Camel parking in New Delhi

At the market in New Delhi

At the market in New Delhi

This kid had amazing European features with blue eyes

At the animal market in New Delhi - very easy going people

New Delhi

Agra

Agra

Agra

On the road in India

Main mosque in New Delhi

Main Mosque in New Delhi

Main mosque in New Delhi

Main Mosque in New Delhi

Old Mosque in New Dehli

Varanasi

Varanasi

Ghats of Varanasi

Holy Ganga in Varanasi

Varanasi

Waiting for cremation in Varanasi

Ganga

Ganga in Varanasi

Preparing for cremation in Varanasi.

Varanasi

Varanasi

Varanasi

Ladakh - traditional outfits

Traditional outfits of Ladakh

Matura, the birth place of Lord Krishna

Matura is full of fascinating people - pilgrims and wanderers

Hard life - this can not be good for you…

Matura - keeping up with the scriptures

Tea vendor in Matura

He was trying to hypnotize me :-)

Lord Krishna rules Matura

Matura

The birthplace of ShriKrishna

Krishna fashions

Matura

Matura

Matura, selling tika

Street food in Matura, not the healthiest but very cheap

Matura

Zanskar Ladakh Traverse in India

Saffron Seller in Manali

The road from Manali to Dacha - our starting point

On the way to Darcha

Darcha, our starting point

The Himalaya around Darcha

Climbing to Shingo La

Shingo La 5,062m

Shingo La 5,062m

Descending from Shingo La to Lakung

View towards Lakung

A friendly tea house in Lakung

On the way to Lakung, descent from Shingo La with Mt. Guburajon 5, 320m behind

Descent from Shingo La not he way to Lakung

Approaching Lakung

Lakung Village

Lakung Mani Wall

Lakung Village, the first village after Shingo La. Mt. Gumburajon 5,320m dominates the horizon.

Lakung Village with Mt. Guburajon on the horizon.

Lakung Village

Mani Wall in Lakung Village

Approaching Changpa Tsetan

Approaching Purne

The incredible Phuktal Gompa where we spent the night.

The Phuktal Gompa is literally built into the mountain.

In Phuktal Gompa.

Phuktal Gompa

Phuktal Gompa

Padum

Karsha Monastery at 3,662m

Karsha Monastery

The view from Karsha Monastery

Karsha

In the Lamayuru Gompa

In Karsha Monastery

Karsha Konastery

The fields around Karsha from Karsha Monastery.

Karsha

On the way from Karsha to Pishu

Between Karsha and Pishu

Leaving Karsha

Pishu Village

Mountains around Pishu Village

Between Pishu and Hanamur

Between Pishu and Hanamur

The view from Hanuma La 4,724m with Lingshed below.

The view of Lingshed Monastery from Hanuma La 4,724m

Descent from Hanuma La 4,724m to Lingshed.

Fields around Lingshed 3,882m

Lingshed 3,882m

Lingshed 3,882m

Lingshed Monastery 3,882m

Lingshed Monastery 3,882m

Lingshed Monastery

Karsha Monastery

Lingshed Monastery

Our camp in Pishu Village

Around Darcha

Around Darcha

Karsha

Descent from Shingo La

Descent from Shingo La

Karsha

View from Karsha

Around Pishu

Between Tabley and Purne

Between Tabley and Purne

Pishu Village

Lingshed

Lingshed Monastery

Lingshed Monastery

Lingshed Monastery

Lingshed Monastery

Singge La 5,009m

Singge La 5,009m looking towards Photoksar Village

Descending from Singge La 5,009m

SirSir La 4,852m

SirSir La 4,852m

SirSir La 4,852m

The view from SirSir La 4,852m

Descent from SirSir Pass to Hannupatta

Between Hannupatta and Phengila

Road construction between Hannupatta and Phengila

Lamayuru

Lamayuru - waiting for Rimpoche

In Lamayuru Monastery

In Leh

Leh

Leh

Leh with Stok Kangri Behind me.

Leh

Uzbekistan - The Heart of the Silk Road

We flew from Tashkient to Khiva, took a car from Khiva to Bukhara, a train from Bukhara to Samarkand and a traimn again from Samarkand back to Tashkient.

Mali - Timbuktu and Djenne

M. Cocheteaux, the French Resident Administrator of the Mopti region, directed the construction of the Great Mosque in 1935. This new mosque was built on the site of a previous one dating from 1908. He is credited with its design as well, basing his efforts on the Great Mosque of Djenne, which had been reconstructed about thirty years earlier. Imitating this "Sudanese" style was a priority for Cocheteaux, but his design is significantly more vertical and symmetrical than Djenne and other regional mosques. The Resident Administrator was also keenly aware of the tourist experience of approaching and viewing the Mosque. Cocheteaux even built two nearly identical facades with this in mind, maintaining the mosque's orientation towards Mecca and its position in the urban environment while creating dramatic views from the city and the river.

The Great Mosque of Djenné is the greatest achievement of Sudano-Sahelian architecture (Sudano-Sahelian refers to the Sudanian and Sahel grassland of West Africa). It is also the largest mud-built structure in the world. Djenné was founded between 800 and 1250 C.E., and it flourished as a great center of commerce, learning, and Islam, which had been practiced from the beginning of the 13th century. Soon thereafter, the Great Mosque became one of the most important buildings in town primarily because it became a political symbol for local residents and for colonial powers like the French who took control of Mali in 1892. Over the centuries, the Great Mosque has become the epicenter of the religious and cultural life of Mali, and the community of Djenné. It is also the site of a unique annual festival called the Crepissage de la Grand Mosquée (Plastering of the Great Mosque).

The Great Mosque that we see today is its third reconstruction, completed in 1907. According to legend, the original Great Mosque was probably erected in the 13th century, when King Koi Konboro—Djenné’s twenty-sixth ruler and its first Muslim sultan (king)—decided to use local materials and traditional design techniques to build a place of Muslim worship in town. King Konboro’s successors and the town’s rulers added two towers to the mosque and surrounded the main building with a wall. The mosque compound continued to expand over the centuries, and by the 16th century, popular accounts claimed half of Djenné’s population could fit in the mosque’s galleries.

At the top of the pillars are conical extensions with ostrich eggs placed at the very top—symbol of fertility and purity in the Malian region. Timber beams throughout the exterior are both decorative and structural. These elements also function as scaffolding for the re-plastering of the mosque during the annual festival of the Crepissage. Compared to images and descriptions of the previous buildings, the present Great Mosque includes several innovations such as a special court reserved for women and a principal entrance with earthen pillars, that signal the graves of two local religious leaders.

The entry into the Djenne Mosque is forbidden for non Muslims. However, for 500CFA Cadieux we were granted access. Unfortunately half way through our tour, the imam made an appearance and we had to run for our lives not to be scolded or worst.

The inner courtyard of the great mosque of Djenne

Luck for us, we were in Djenne on the market day. It was a busy place with many people hiking in from surrounding villages.

Kola nuts are the currency of the Sahel. Kola nuts are used as a religious object and sacred offering during prayers, ancestor veneration, and significant life events, such as naming ceremonies, weddings, and funerals. They were used as a form of currency in such West African groups as the Malinke and Bambara of Mali and Senegal. They are still used as such today in certain situations such as in negotiation over bride prices or as a form of a respect or host gift to the elders of a village should one move to a village or enter a business arrangement with the village.

Market day in Djenne

The Djenné Manuscript Library is housed in a handsome two-storey traditional Djenné mud building just to the south of the Great Mosque. It was built in 2006 with the support of the European Community Fund and the Embassy of the United States of America. In 2007, a management committee made up of notable Djenné residents was put in place; their task was to ensure that the library remained the property of the whole population of Djenné, and continued to provide a safe repository for the manuscripts from private family collections. The deposited manuscripts remained the property of their owners. The library is therefore a public space housing private collections: an original model, entirely different from that of Timbuktu which has in the region of fifty small separate private family libraries which are housed in the individual homes of the collectors.

Mount Hombori, the highest point in Mali

Hombori village and Mount Hombori

Tuareg Tribesmen in the Sahara

Preparing for the evening prayer. Sahara desert near Timbuktu.

Evening prayer

Timbuktu - town square. Djingareyber mosque main minaret is behind.

A Tuareg tribesman

Located at the gateway to the Sahara desert, within the confines of the fertile zone of the Sudan and in an exceptionally propitious site near to the river, Timbuktu is one of the cities of Africa whose name is the most heavily charged with history.

Founded in the 5th century, the economic and cultural apogee of Timbuktu came about during the15th and 16th centuries. It was an important centre for the diffusion of Islamic culture with the University of Sankore, with 180 Koranic schools and 25,000 students. It was also a crossroads and an important market place where the trading of manuscripts was negotiated, and salt from Teghaza in the north, gold was sold, and cattle and grain from the south.

The Djingareyber Mosque, the initial construction of which dates back to Sultan Kankan Moussa, returning from a pilgrimage to Mecca, was rebuilt and enlarged between 1570 and 1583 by the Imam Al Aqib, the Qadi of Timbuktu, who added all the southern part and the wall surrounding the cemetery located to the west. The central minaret dominates the city and is one of the most visible landmarks of the urban landscape of Timbuktu.

Built in the 14th century, the Sankore Mosque was, like the Djingareyber Mosque, restored by the Imam Al Aqib between 1578 and 1582. He had the sanctuary demolished and rebuilt according to the dimensions of the Kaaba of the Mecca.

The Sidi Yahia Mosque, to the south of the Sankore Mosque, was built around 1400 by the marabout Sheik El Moktar Hamalla in anticipation of a holy man who appeared forty years later in the person of Cherif Sidi Yahia, who was then chosen as Imam. The mosque was restored in 1577-1578 by the Imam Al Aqib.

The three big Mosques of Djingareyber, Sankore and Sidi Yahia, sixteen mausoleums and holy public places, still bear witness to this prestigious past. The mosques are exceptional examples of earthen architecture and of traditional maintenance techniques, which continue to the present time.

The Djinguereber Mosque is a famous learning center of Mali built in 1327, and cited as Djingareyber or Djingarey Ber in various languages. Its design is accredited to Abu Es Haq es Saheli who was paid 200 kg (40,000 mithqals) of gold by Musa I of Mali, emperor of the Mali Empire. According to Ibn Khaldun, one of the best known sources for 14th century Mali, al-Sahili was given 12,000 mithkals of gold dust for his designing and building of the djinguereber in Timbuktu.

Djingareyber mosque

Djingareyber mosque

Djingareyber mosque

Traditional door of Timbactu

A Tuareg camp in the desert

Mali - The Niger River

Our route was from Timboctou to Bamako

Mali - Dogon Country

The principal Dogon area is bisected by the Bandiagara Escarpment, a sandstone cliff of up to 500 m (1,640.42 ft) high, stretching about 150 km (90 miles). To the southeast of the cliff, the sandy Séno-Gondo Plains are found, and northwest of the cliff are the Bandiagara Highlands. Historically, Dogon villages were established in the Bandiagara area a thousand years ago because the people collectively refused to convert to Islam and retreated from areas controlled by Muslims.

Dogon insecurity in the face of these historical pressures caused them to locate their villages in defensible positions along the walls of the escarpment. The other factor influencing their choice of settlement location was access to water. The Niger River is nearby and in the sandstone rock, a rivulet runs at the foot of the cliff at the lowest point of the area during the wet season.

Among the Dogon, several oral traditions have been recorded as to their origin. One relates to their coming from Mande, located to the southwest of the Bandiagara escarpment near Bamako. According to this oral tradition, the first Dogon settlement was established in the extreme southwest of the escarpment at Kani-Na.

Kani-Kombole Mosque

Kani-Kombole Mosque

Kani Kombole Mosque

Celebration of Tabaski in Kani Kombole on Dec 31

The Imam

The mosque in the village of Ennde

The Ennde mosque

The Ennde Mosque

Dogon Taxi

We travelled on an ox cart from village to village

Dogon Taxi

Tellem

The village of Tellem

Villages are built along escarpments and near a source of water. On average, a village contains around 44 houses organized around the 'ginna', or head man's house. Each village is composed of one main lineage (occasionally, multiple lineages make up a single village) traced through the male line. Houses are built extremely close together, many times sharing walls and floors.

Dogon villages have different buildings:

Male granary: storage place for pearl millet and other grains. Building with a pointed roof. This building is well protected from mice. The amount of filled male granaries is an indication for the size and the richness of a guinna.

Female granary: storage place for a woman's things, her husband has no access. Building with a pointed roof. It looks like a male granary but is less protected against mice. Here, she stores her personal belongings such as clothes, jewelry, money and some food. A woman has a degree of economic independence, and earnings and things related to her merchandise are stored in her personal granary. She can for example make cotton or pottery. The number of female granaries is an indication for the number of women living in the guinna.

Tógu nà (a kind of case à palabres): a building only for men. They rest here much of the day throughout the heat of the dry season, discuss affairs and take important decisions in the toguna. The roof of a toguna is made by 8 layers of millet stalks. It is a low building in which one cannot stand upright. This helps with avoiding violence when discussions get heated.

Punulu (a house for menstruating women): this house is on the outside of the village. It is constructed by women and is of lower quality than the other village buildings. Women having their period are considered to be unclean and have to leave their family house to live during five days in this house. They use kitchen equipment only to be used here. They bring with them their youngest children. This house is a gathering place for women during the evening. This hut is also thought to have some sort of reproductive symbolism due to the fact that the hut can be easily seen by the men who are working the fields who know that only women who are on their period, and thus not pregnant, can be there.

Ireli

Ireli

Tellem

Tellem

Ireli

Tellem

The fetish houses in Tellem

The fetish houses in Tellem

Fetish houses in Tellem

Tellem

During the eleventh century, a hunter-gatherer group known as the Tellem constructed dwellings high on the cliff face as protection from raiders and hostile neighbors. Along with occupying caves on the escarpment face, the Tellem built cylindrical granaries in shallow recesses of the rock. Possibly as a result of conflict with the Dogon and neighboring groups, the Tellem---described by the Dogon as “the ones we found”---abandoned the escarpment sometime in the 1800s, leaving behind pottery, baskets, leather bags used to carry water, jewelry, and other items.

Village bell

A goat being prepared for the celebration of Tabaski

Tógu nà (a kind of case à palabres): a building only for men. They rest here much of the day throughout the heat of the dry season, discuss affairs and take important decisions in the toguna. The roof of a toguna is made by 8 layers of millet stalks. It is a low building in which one cannot stand upright. This helps with avoiding violence when discussions get heated.

Baffin Island - Stewart Valley and Sam Ford Fjord

Sam Ford Fjord is an isolated and L shaped Arctic fjord, which is located on the Northeastern coast of the Baffin Island in the Arctic Archipelago, in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Canada. The fjord stretches for approximately one hundred and ten kilometers and was traditionally one of the hunting areas of the Inuit, popularly known for its spectacular granite cliffs (some of them are the highest cliffs in the world) which rise high from the shores. We decided to explore it on Skis in early May. There were 3 of us: Jerry Kobalenko, David Holberton and me. We hired an outfitter from Clyde River, a small Inuit settlement on the shores of Baffin Island, to take us to the end of Stewart Valley by a skidoo. Our plan was to ski back and explore points of interest along the way. It was still winter and I never really got warm throughout the trip.

In 2012 I was flying from London to Calgary over the Sam Ford Fjord with good visibility.

Sam Ford Fjord. We traveled across the fjord in roughly in the middle of the photo. Sam Ford Fjord (Kangiqtualuk Uqquqti) stretches roughly from north northeast to south southwest for about 110 km (68 mi). Its mouth, located between the Remote Peninsula and Erik Point, is over 18 km (11 mi) wide, the width of the fjord narrowing gradually to an average of 3 km (1.9 mi) about 50 km (31 mi) inland. Kangiqtualuk Agguqti is a tributary fjord branching west from the fjord's western shore about 45 km (28 mi) to the south of its mouth. The Stewart Valley —with Sail Peaks stretches northwards from Walker Arm's nortwest corner and connects with the neighbouring Gibbs Fiord.

Sam Ford Fjord. The Polar Sun Spire is visible as the pointy peak down from the center of the photo.

The peaks from the areal photo above on Jerry Kobalenko’s photo

Photo by Jerry Kobalenko

This is how we transferred ourselves and our gear to the start of the trek. The outfitter mainly helps with polar bear hunting.

Approaching the Sam Ford Fjord.

It took us 8 hours of travel from Clyde River to the end of Stewart Valley. By the time we arrived at our destination, I was completely frozen despite wearing all the clothes I had.

Approaching Sam Ford Fjord. The scenery was getting more and more spectacular.

In the Sam Ford Fjord

Skiing under the Great Sail Peak. Great Sail Peak rises 1617m and like its neighbor (Polar Sun Spire) is located near the Sam Ford Inlet, in nearby Stewart Valley. The peak is located to the north and to the east of Polar Sun Spire and is the lone 'big wall' in its region (if one excludes numerous walls that range from 500-700 meters).

Looking back at the Stewart Valley and the Great Sail Peak (on the right).

Our camp below the Walker Citadel in the Walker Arm of the Sam Ford Fjord

The frozen lake in the Stewart Valley

Stewart Valley and the Great Sail Peak in the distance.

The Great Sail Peak

David and I skiing under the Great Sail Peak (photo by Jerry Kobalenko).

Our camp 2 at the foot of the Great Sail Peak

Walker Citadel and the spectacular walls of the Sam Ford Fjord

Stewart Valley

The expanse of rock of the Walker Citadel is dwarfing David and Jerry

Approaching Walker Citadel

Our camp on the sea ice at the foot of the Walker Citadel

Looking up the Walker Arm

Skiing towards the Sam Ford Fjord

Our camp in the Sam Ford Fjord

David Holberton

Jerry Kobalenko

Clyde River

The community of Clyde River

Sam Ford Fjord

Great Sail Peak

In the Sam Ford Fjord

This was our kitchen each night

Skiing in the Sam Ford Fjord

Under the Polar Sun Spire

Our camp in The Sam ford Fjord

Bylot Island Expedition Trip Report

The map is from the 2018 ACC Journal. It is not our expedition referred to on the map but it covers the general area where we were. All around Sermilik Glacier.

Bylot Island Expedition Report August 2006 (based on the journal of David Holberton)

The expedition to Bylot Island in the Canadian Arctic was undertaken by Derek, David (our Brit Extraordinaire), and Dave, who lives and works in the Inuit village of Pond Inlet, on the NE coast of Baffin Island. Dave Reid was the last Scot ever to the recruited by the Hudson Bay Company, in the late -1980s; now he is the local “Mr. Fix it” for expeditions, research projects and the like.

Pond Inlet (“Pond”) is accessible via the scheduled air service of the Inuit-owned airline, First Air, 2.5 hours flying from Iqaluit, or 4 hours with a stop in Clyde River. David and I met in Ottawa and flew up to Iqaluit from there. Pond is a village of some 1,500 people. It is a relatively new place, founded in the 1920s, and has only significantly expanded since 1970s when previously nomadic families settled there permanently. There is a big government presence, a dirt airstrip and a developing iron-ore mine to the south: all these provide some employment, but otherwise the population still survives on hunting (polar bear, seal, narwhal, geese) and inevitably, on government handouts.

Directly from the airstrip we could see the wall of snowcapped mountains on Bylot Island, 20 miles away across Eclipse Sound. They rise straight out of the sea up to more than 6,000 feet. We had planned to go over to the island immediately, but our plan was thwarted by the rough sea and the time taken to deal with Parks Canada bureaucracy. In fact, the orientation session was run by one of the wardens, Israel, whom we had met two years before on Ellesmere Island. He recognized us straight away! Pond is his home, and he is clearly delighted to be back here with his family, instead of being posted to the remote Tanquary Fjord station on Ellesmere. Orientation is mandatory and it is supposed to educate visitor on sound environmental practice, how to deal with polar bears etc. We have heard it all before, and the Park’s staff merely shows videos and read from a prepared script. It is a bit like a safety briefing on an aircraft.

Bylot Island is part of Sirmilik National Park, the fourth largest in Canada, but one of the least visited. It was created only in 2001. Simirlik means “place of glaciers” in Inuktitut, and indeed the island is characterized by a large number of glaciers originating from an ice cap in the central region. The island is 50 miles N to S and 100 miles E to W. It is uninhabited: during our trip we were the only people on the island apart from two bird researchers camped on the western side. Much of the island has never been explored. The N to S crossing by Tillman in August 1963 is perhaps the well known; it is recounted in his book Mostly Mischief. Otherwise visitors have tended to gravitate toward specific areas: the climbing interest is in the 3 highest peaks, Thule (1,711m), Angilaaq and Mitima, which are to the west side of the Sermilik Glacier. This is one of the biggest glaciers, which reaches the sea directly opposite Pond. The bird researchers gravitate toward the west coast of the island. The entire island is a designated bird sanctuary. It is the northern end of the migration route of the greater snow goose with more than 250,000 birds on the island in the summer.

The particular hazard for us was the polar bear. There are 150 of them in the island. They are commonly seen on the beaches but more on the north side of the island than on the south. We planned not to spend very much time on the beaches for that reason. We were armed only with bangers and flares as it is prohibited to carry a firearm in the National Park. We were fortunate to have seen only paw prints in the sand.

During our enforced stay in Pond that first day, we made two critical decisions. One was to split the trip into two parts, leave half the food and some spare gear on the beach in bear proof barrels, and therefore reduce our load somewhat. The second decision was to take only one tent and squeeze the three of us into it, again saving weight. The North Face Mountain 25 is after all designated as a 3men tent J! We could see the immediate pros of these decisions. The cons were only apparent later.

Next morning we were able to leave at about 10am in the small boat owned by local hunter Sheatie Tagak. The 20-mile ride across the sound was $500. We were kitted out in orange survival suits. The sea was glassy calm and we had a fast ride across the sound in just 45 minutes, to a point just east of the toe of the massive Sermilik glacier.

On the way across the sound, we passed by huge icebergs that originate from Greenland or Ellesmere Island and are swept into and around Eclipse Sound by the current. On the beach we sorted our heavy packs and were off. Despite our weight saving measures, our packs still weighted in at around 40lbs. The crampons, ice axes and other mountaineering gear count for a lot of that. We were over the moraine and on the glacier within an hour. All the snow having melted we could walk easily on the ice without crampons, any crevasses being obvious and easily negotiated. After lunch we turned further west onto a side glacier, big enough in itself, and crossed over to the west side where we camped on the ice at the foot of a steep incline.

The following day we headed further up the glacier in a northerly direction. An interesting peak appeared to our right, and we resolved to seek out routes to the top. Camping beneath its south-west spur, with excellent views down the glacier all the way to the sea, we walked further to the north and up the scree on the north side, but this rock band was simply too steep and too loose to be a viable option.

On the third day, in bright sunshine, we looped back south and then west into a huge bowl of snow and ice that gave us easy access into the southwest ridge, with just a short section of ice where crampons were required. On top of the ridge the ice gave way to more rock – all of it loose – but we could scramble up the ridge quite easily until the summit became visible across a broad saddle. Here we left our packs and continued with crampons and ice axes up the last 600 ft. At the summit, altitude 5,250 ft. (1,600m), we had a splendid 360-degree view, with visibility at least 50 miles into the dark fjords on the north coast of Baffin Island. On Bylot Island itself we could see the whole panorama of snowy peaks and huge glaciers running in all directions. Except to the NE that was covered in cloud, with just a few summits peaking above. This was some of the finest mountain scenery you could imagine, certainly on par with what we saw last year in Pakistan. The summit, we think, has never been climbed before. Dave would check the records with the Alpine Club of Canada. We named the peak Fugoy Fang (Tenzing Fugoy is my Chinese name and since I stepped on the summit first, I claimed the naming rights :-)).

Although we had to retrace our steps to some extent we did descend the more direct but steep northern side of the SW spur. The first part on loose rock and then on snow and ice. It appeared doable from above, but when we looked back afterwards it looked vertical and did require total concentration. We returned to our camp at 6pm, a long but rewarding 9-hour day.

In our evolving route plan, we had decided to try to cross a pass on the other side of the glacier and descend onto the Sermilik glacier, where we could relatively quickly travel down to the beach to resupply. The pass was a lower altitude than the peak we had summited, but we would have to carry full packs, and the top section looked to be very steep. However, there was no harm in taking a closer look, as we always had the option of going back the way we came. In fact, reaching the top of the pass was quite easy, it took us just over 2 hours. We could follow a rock band on the north side most of the way and only required crampons for a short section at the end. Again, we had fine weather and excellent views from the pass – looking back over our entire climbing route of the previous day, to the east, and the vast ice field of the Sermilik glacier to the west.

Of course we had no idea what the descent would be like and this is where the adventure really began. To begin, we spent an hour traversing a steep exposed ice slope. David and I brought leather 4-season boots that can be securely fitted with crampons, but they do not give the ankle support you would get with plastic mountaineering boots, and they make the fit of the boot much tighter. The huge exposure was unsettling, as we were not roped up. There was no place to rest and it would have been difficult to self-arrest in hard ice had any one of fallen. We did not rope up for that reason. We were rewarded with a lunch stop on a rocky knoll, which was surely one of the finest picnic sites in the world, high above Sermilik glacier.

The reminder of the descent looked dauntingly steep. We had little choice except to follow the scree straight down, but this scree was our worst nightmare. The rocks were large and as loose as loose could be and the angle of the slope was near vertical. In negotiating this it was every man for himself – no way for the others to help quickly or at all of required. Of course we had to carry our weighty packs down this slope, which as really far too steep for backpacking. We collected ourselves at the foot of the slope; again we looked back and shook our heads in amazement at the steep slope we had negotiated. Had we been traveling in the opposite direction, there is no way we would have considered an ascent. That was another long day, and it was too ambitious by far to get to the foot of the Sermilik glacier today.

That night we camped in the middle of the Sermilik glacier about 5 miles from the toe. On the fifth day, the plan was to descend on the right (west) side of the glacier, leave our packs at a suitable campsite on the moraine, then skirt along the beach, around the toe of the glacier to pick up the new food supply from the barrels, which we left at the east side of the glacier. At the outset, none of us could have guessed what a ridiculously ambitious plan this would prove to be. We were walking at just over 1 mile an hour with full packs, and the glacier proved to be heavily crevassed on the west side, with plenty of valleys carved out by the glacial streams. It took time and effort to cross these, after which for the first time we came to a river crossing. River crossing is an inevitable and frequent part of Arctic backpacking. We carried TEVA sandals (easy to change into, good footing but no respite from cold water) or neoprene booties (a struggle to put on and off, you can feel every stone underfoot, but they are warm) for the purpose, and edged our way using trekking poles to gauge depth and speed of the water. Changing into/out boots all takes time. So it was not until 4pm that we were ready to leave the campsite to go in search of the food barrels.

Our journey turned into a nightmare, because we found that the glacial outwash along the beach was braided into numerous deep and cold fast –flowing rivers, and the distance between the toe of the glacier and the open sea – perhaps 200 meters – was insufficient, too much of a gradient to create shallower water where we could safely cross. After the first couple of crossings, we decided to go over the glacier instead, which was easily accessed from the beach. But after an hour of wandering around on the ice, it was apparent that we would need to walk a very long way back in order to safely negotiate the undulating ice valleys and surface glacial streams. So we abandoned that idea and returned to the beach.

We tried again to cross the series of rivers emptying from the Semirlik glacier. It was on our fourth river crossing that we nearly fell in (the result of which would be a quick ride to the Arctic Ocean). Instead of walking directly across, we walked halfway across and the up the middle to find a shallower route for the second half. But the current grew stronger and the depth greater until we were mid-thigh in freezing cold water. You could see big blocks of ice floating in the torrent, as the glacier was very near. Although we made it to the other side it was too close for comfort, and we knew it. Dave and I looked at each other and started laughing: we knew it was a lucky escape. The golden rule is that if the water is more than knee deep it is not safe to cross. We had broken that rule.

I was hit by one large piece of ice and the force of the water took away one of my booties (we had a spare pair of TEVAS). I was also bleeding but I did not feel a thing due to the cold-numbing water. We started to worry a bit, seeing the glint in Dave’s eyes: he was on a Canute-like mission to reach the barrels and no force of water was going to stop him.

So eventually at 7pm David called a halt and asked whether this was a sensible thing to do (this is a British way of saying, "This is completely mad and dangerous, let's stop!!!"). After some discussion we decided to abandon the barrels for that day, take a rest day the following day, and then try again the day after that. We would try very early in the morning as we were expecting the water level to be lower at that time of the day.

We had a plan B to do the second half of the trip immediately, with what food we had left, but it was clear that we would be hungry. Added to that we needed some rest. From our position merely half way across the glacier runoff, we returned to the campsite, which was an adventure in itself: a very long way with many ups and downs and difficult crossings of glacial streams. It was the coldest crossing EVER and set a new tolerable level of coldness of me. My legs felt like two wooden pegs. In the evening, when temperatures fall, the surface ice of the glacier starts to harden and it is more difficult to keep the grip, bearing in mind that we had only trekking poles for support and no crampons. We eventually made it to the campsite at 9 pm – an exhausting 12-hour day.

After a well-deserved rest day we rose at 5am to make another attempt to retrieve the barrels. It was all in vain. It was quickly obvious that the water was just too fast and to deep to cross safely. It was also so cold at this hour that it was painful to be in it. Our skin turned lobster-red at the slightest immersion. There was nothing to do, but call for help. Fortune was on our side as the ever-helpful Sheatie was at home =, and with the help of another $500 hopped in his boat and helped us transfer the barrels over to the west side of the glacier (his wife was less impressed as we woke her up with our early morning sat phone call). By lunchtime we were restocked, packed and ready to go for the second part of our trip: the planned ascent of Mt. Thule.

Once clear of the moraine, we found ourselves in a green and pleasant valley, of rushing rivers and tundra underfoot. We crossed two rivers that presented no problem, and then climbed steeply over the moraine of the Stagnation Glacier – so called because of its dramatic retreat in the recent decades – before we returned to the tundra and found a campsite, on a soft knoll overlooking the vastness of a large glacier on the south side of the valley. In contrast to the Stagnation Glacier, this glacier barely moved an inch in the same period. The difference is attributed to relative size and the northerly direction of the latter versus the south-facing Stagnation Glacier.

Despite our plans we were forced to stay for three nights, as the weather turned and we had continuous rain for 24 hours. It was clear that the ascent of Mt. Thule would be abandoned as all of the tops were clouded in: there is no point going to the top in the rain if there is nothing to see. During that time, the downside of the “3 Men” North Face tent became apparent: it was simply too small for comfort.

We were laying head to toe with David in the middle. His feet were between the shoulders of Dave and I. The discomfort and restless nights just added to the difficulty of the trip. We all admitted how tired we were; perhaps it was a good thing that we did not have the conditions to climb Mt. Thule. It would have been another long and demanding day.

On the second day, when we could really tolerate not one moment more in the tent, we hiked up directly in front of the huge face of the glacier to the nearest summit, much of it on the tundra and then a long ridge of more loose rock. Dave was absolutely gung-ho to get to the summit and was worth it for the views: you could see far away to the southwest all the way to the coast and beyond to Baffin Island.

Monday, August 14 was theoretically our last day, but due to the strong winds, Sheatie could not pick us up. We were starting to worry as we could miss our flight home. We spent the final day walking on the long beach. We found big sandstone cliffs with weird shapes – known as “hoodoos – carved out by the wind and rain, perfectly rounded rocks like Moeraki boulders in New Zealand but smaller, and huge boulders inlaid with beautiful patterns like marble. The beach is always a special place, and this was no exception, although noting the presence of bear prints, we were careful to keep our eyes skinned. This area, which is not part of the Park, has been a camping area for the local Inuit for a long time, and was strewn with the bones of seal and narwhal.

That evening, a terrific wind blew up and continued blowing all the next day. It was clear there would be no boat pick-up in those conditions. Inside the tent there was respite from the wind, and warmth, but it was incredibly noisy as the wind continuously shook the fabric. We revisited the hoodoos, this time more impressive with blue skies for background and sunshine to accentuate the color, but it was cold and the cold wind sapped our will to spend too much time outside. By evening we were rather worried as there was no let up in the wind and we did have a plane to catch the following day. But at 4.30am there was a sudden flurry of activity as Sheatie was on his way. It turned out that although this did co-incide with a lull in the wind, Dave had been motivated to peek his head out and assess the weather conditions more by his urgent desire to escape the tent. By that point we had spent so many hours in it that any opportunity to get out was not to be missed, no matter how early the hour (as we had 24 hour daylight, hours did not much matter anyway).

We waited for an hour on the beach. We tried to find the calmest spot on the beach, the current and wind dragged the anchor and pushed the boat sideways on, so it was a real struggle to push the bow into the waves and get off the island. At this point we were down to the last bits of food, so it was a relief to pick up the barrels again, and raid the emergency supply of soggy digestive biscuits. The ride across the Eclipse Sound was rough with large waves at out comfort limit. We were getting sprayed by the cold water and were totally soaked by the time we arrived in Pond.

A quick goodbye with Sheatie and we were off to the local hotel for a plate of eggs and bacon.

When we look back on it in years to come, we – and I include Dave, as a fellow traveler not “the leader” - will have fond memories of the expedition. For the fact that we went places and climbed mountains where no one has ever been or climbed before: what a sense of achievement and spirit of exploration in the world were every place has been penetrated. For the excellent company and the temperament of the three of us: we laughed a lot and never argued about anything. For the dangers and risks actual and potential with we faced and overcame. And above all for the privilege of traveling in this wild and remote place.

Bylot Island Sermilik National Park Exploration in the Canadian High Arctic

Sermilik National Park is located at the northern end of the Baffin Island and on the Bylot Island amid an expansive landscape of glaciers and mountains rising from iceberg-dotted waters of the Arctic Ocean. Sermilik means the ‘place of glaciers’ in Inuktitut. Vast glaciers flow from an ice cap located in the middle of Bylot Island into nearby Eclipse Sound. Our goal was to climb Mt. Thule and some other unclimbed peaks along the Simirlik Glacier and to explore the Bylot Island's vast glacier system. Our group consisted of David Holberton, David Reed and me. We hired Shaty, and Inuk from Pond Inlet, to take us across the Eclipse Sound.

The map is from the ACC Journal. This is not our ski expedition but we trekked in the same area between the Sermilik Glacier/Mount Thulie and Koperoqtwlik Glacier.

Pond Inlet on the north side of the Baffin Island

Pond Inlet with the Bylot Island in the distance - our destination

Pond Inlet

Leaving Pond Inlet for our Bylot Island exploration

Landing on Bylot Island

Sorting our food for the next two weeks

We decided to follow the Sermilik Glacier and climb the highest unnamed mountain on the horizon. We were probably the first people that climbed it.

This is an areal view of the glacier and the mountain we climbed. The peak is the highest one in the background on the center-right. As far as we knew no one has climbed it before us. Since I was the first on the top, I named it using my Chinese name Fugoy Fang. (photo credit unknown)

Massive glaciers and unclimbed peaks

Our objective is now directly ahead hidden in the clouds.

The scale of the terrain is very grand. It is deceptive since there are no reference points.

Photo by David Holberton

We crossed an unnamed mountain pass to access a large glacier system

Glacier rivers

Glacier rivers- deadly if you fall in

Massive Sermilik Glacier flowing from the centre of the island

Sermilik Glacier

A large river flowing into the Arctic Ocean from the massive Sermilik glacier

Preparing to ford a river

Eclipse Sound

Pond Inlet

Canadian Army in the North in Pond Inlet. They get a cool looking t-shirt and maybe a gun.

Atacama, Incahuasi in northern Argentina

We set out to climb the volcano of Incahuasi, a mountain on the border of Argentina and Chile. Incahuasi has a summit elevation of 6,621 metres (21,722 ft) above sea level. We flew from Buenos Aires to La Rioja in Northern Argentina and then drove to Fiambala, the border outpost. There, we met our driver Johnson who arranged for our transport to Las Grutas, a border police post close to Incahuasi. We had two main issues: acclimatization and water. The mountain is very high and there is no drinkable water. We were counting on the winter snowpack to provide us with the source of water. Unfortunately, we did not find any snow and had to abandon our attempt. The trip gave us a great opportunity to trek through the little visited corner of the Atacama Desert. It was a good adventure regardless of our lack of success with the summit.

The border post between Argentina and Chile. Since the mountain Incahuasi is on the border, we need to clear the customs. We will be in no man's land.

Cerro San Francisco

Volcanic landscape of Incahuasi

Hard work at 5000m

The summit of Incahuasi is 1000m above

The summit of Incahuasi ahead

View from the high up on Incahuasi

Looking for snow to melt - not much is available

Our basecamp at the foot of Incahuasi

The Altiplano

The Altiplano - walking back to Argentina

The beautiful Altiplano

The Atacama - the driest place on earth

The water is full of poisonous chemicals like arsenic

La frontera de pais

Patagonia - Southern Patagonian Ice Field

Approaching the village of El Chalten

Cerro Marconi Norte is just ahead - we want to go to the top of it

Fitz Roy

Fitz Roy

Paso Marconi in relentless Patagonian rain

Our camp on Paso Marconi. After the drenching rain we woke up to clear sky and sunshine. We needed it to dry off everything.

Paso Marconi and Gorra Blanca

Paso Marconi and Cerro Marconi Norte

Walking up Cerro Marconi Norte

Cerro Marconi Norte and Fitz Roy in the background

The view over the Paso Marconi

Southern Patagonian Icefield

Volcan Lautaro and Southern Patagonian Icefiled from Cerro Marconi Norte

Gorra Blanca, Paso Marconi from Cerro Marconi Norte

Fitz Roy from Cerro Marconi Norte

Southern Patagonian Icefield from the air - Fitz Roy and Cerro Torre on the right

The expanse of the Southern Patagonian Icefield

Southern Patagonian Icefield

Hiking on ice

Our camp at the Cirque de Los Altares

Awesome clouds of southern Patagonia

Cerro Torre

Cerro Torre from Cirque de Los Altares

Cerro Torre

Cerro Torre

Base of the Cerro Torre

Summit snow mushrooms of Cerro Torre

Looking up Cerro Torre from its base - now it looks like a real tower

Cirque de Los Altares

Inside the Cirque de Los Altares

Cirque de Los Altares

Our camp on the Icefiled in front of the Cirque de Los Altares

Good weather does not last...

Horizontal rain of Patagonia

Glaciar Viedma

Glacier Viedma

Glacier Viedma

Lago Viedma - looking for condors

Glacier Viedma and Lago Viedma

Waiting for a ride on Lago Viedma

Glacier Perito Moreno

Perito Moreno Glacier

Perito Moreno Glacier from the air

Patagonia

Patagonia

Southern Patagonian Icefiled

Fitz Roy and Cerro Torre from the air

Gorra Blanca

Cerro Torre group and the Cirque de Los Altares

Cerro Torre

Southern Patagonian Icefield

Fitz Roy Group and Glacier Viedma

Patagonia

Pakistan Snow Lake Hispar Pass

In July of 2005 our small group traversed the Biafo and Hispar Glaciers in the Karakoram Mountains of Northern Pakistan. The two glaciers are connected by the 5,128 Hispar Pass. Along the way, we camped and explored the Snow Lake, one of the largest expanses of ice in the Karakoram Mountains.

Biaffo, Choktoi and Nobade Sobande Glaciers.

Nanga Parbat, we arrived in Islamabad on June 19. We were unable to get on the flight to Skardu in Baltistan and drove in a big private bus instead. We stopped in Chilas at the K2 Motel after a 12 hours drive at the half way point between Islamabad and Skardu.

Nanga Parbat - the view from near Chilas.

Nanga Parbat

Nanga Parbat

The meeting point of the Hindu Kush, Karakoram and the Himalaya mountain ranges

Remains of the Buddhist culture in northern Baltistan (a point of interest along the ancient Silk Road)

Karakoram Highway

Balti fast food in Skardu. We arrived in Skardu on June 20th. We got up early the following morning to take photos of Indus River sand dunes. In Skardu, we stayed at the Pioneer Hotel.

The Indus River valley near Skardu in the evening.

The Indus River near Skardu

The early morning light on the sand dunes of the Indus River near Skardu.

The sand dunes of the Indus River

Sand dunes of the Indus River

We drove from Skardu to Askole. The drive is 6-7 hours long and follows the Shigar and Braldu River Valleys. The road was blocked by a rock fall but the locals blasted the passage open. The photo is of a bridge over the Braldu River near Askole.

The bridge over the Braldu River near Askole.

Jeep track from Skardu to Askole. We were blocked by a rockfall.

The road from Skardu to Askole along the Braldu River. Askole is at 2,965m.

The spot where the trail to the Baltoro Glacier and K2 meets the trail to the Biafo Glacier, a 3 hours walk from Askole. During Day 1 on June 22, we hiked on a steep trail through a narrow notch in the cliffs before we could descend to gain the glacier proper.

Day 1. The view to the Biafo Glacier before we descended to it. Our destination for the day was Namla camp at 3,263m. We hiked for 7 hours from Askole. On the way, we got lost in the middle of the Biafo Glacier.

Day 1. Hike from Askole to Namla Camp.

Day 1. Hike from Askole to Namla Camp.

Day 1. Hike from Askole to Namla Camp.

Day 1. Hike from Askole to Namla Camp. Biafo Glacier is visible below.

Dai 1. This was our lunch spot. After lunch we descended to the Biafo Glacier.

Day 1. Biafo Glacier - en route to the Namla camp.

Day 1. The frontal part of the Biafo Glacier.

Day 1. Our crew taking a rest on the Biafo Glacier

Glacial stream on the Biaffo Glacier.

The view from Namla Camp at 3,263m.

Day 2. En route to Banta camp. We initially had to follow the rubble of the lower glacier but soon we started walking on the medial moraine.

Day 2. En route to Banta camp. Walking up the 67 km long Biaffo Glacier

We arrived at the Banta I camp at 3,263m. From here we hiked up to the hills above the camp. We had fantastic views of the Ogre and the Latok mountains. The prominent tower on the left is the Ogre's Thumb, to its right is the Ogre 7,285m. Ogre II 6,960m is the triangular peak to the right. On the left is the Latok group. From the back: Latok 2, 7,086m, Latok 1, 7,151, and small peak of 6,034m.

The Ogre and the Latoks above Banta I camp.

The Biafo Glacier. The Banta Camp is below.

The Biafo Glacier.

The Latok Group.

The Ogre and the Ogre's Thumb

Latok 2 - 7,076m and the triangular pyramid of Latok 3 in the back.

The Ogre 7,285m and Banta Brakk II (Ogre II), 6,960m

The Uzun Brakk Glacier from the hills above the Banta I Camp. Ogre 1 and 2 are on the left.

The Ogres and Latoks from the hill above Banta camp.

Day 3. We could not find a safe way along the glacier. One of the porters climbed a large boulder to find the way. We slogged all day along the Biafo. We encountered deep snow and the going got tough for the porters. We decided to wait until the following morning for the soft snow to freeze. Furthermore, our guide got ill with a stomach ailment.

Day 3. On June 26th and June 27th we camped at rocky ridge in the middle of the glacier at 4,385m.

Our camp on Day 3 and Day 4 in the middle of the Biafo Glacier at 4,385m. We needed a rest day to allow our guide to recover from his illness. We could not hike anywhere during the rest day as we were surrounded by hidden crevasses.

During Day 3, we were trying to negotiate soft snow in the blazing sun.

Negotiating soft snow on the Biafo Glacier during Day 3.

The peaks along the Biafo Glacier.

The morning of Day 4, we had a cold but clear morning on the Biafo Glacier. We were now at 4,385m. The sunrise was quite spectacular illuminating the peaks lining the Biafo Glacier to the north of our camp. We decided to take a rest day to allow our guide to recover from his stomach ailment.

Sunrise on Day 4 at 4,385m

Sunrise on Day 4

Day 5, June 28th. We started early to avoid soft snow again. It was quite cold as we were walking in the shade. We passed below Nagpogoro (black rocks) and Marpogoro (red rocks).

Upper Biafo Glacier

Looking back from the trail between the Biaffo Camp and Lukpe Lago camp on Day 5.

Day 5. En route to Snow Lake (Lukpe Lawo).

Biafo Glacier, looking towards the Latok Peaks. Biafo Glacier here is at the altitude of 4,428m

Day 5, en route to Lukpe Lawo.

Ghur from Biafo Glacier and Game Sokha Lumbu (6,282m)

Day 5, we can now see the Snow Lake ahead. Sosbun Brakk 6,413m is on the left.

Day 5. Approaching the camp on the Snow Lake at 4,745m. We were intending to stay there for a few days to explore the area. The hidden crevasses posed a threat though as the snow would get soft in the intense sun.

Biafo Glacier, approaching the Snow Lake. Sosbun Barak 6,413m is ahead.

Approaching the Snow Lake, Sosbun Brakk (6,413m) towers over the Biafo Glacier. The Hispar Pass is hidden on the left.

Broad Tower (5,063m) and Solu Peak (5,901m)

On the Snow Lake. Broad Tower (6,063m) and Solu Peak (5,901m)

Day 5 and Day 6. Our camp on the Snow Lake at 4,745m.

Snow Lake, looking north east.

The view from our camp at the Snow Lake at 4,745. Day 5 and Day 6.

Cooking area on the Snow Lake

Shirkan in our camp at Snow Lake at 4,745m.

The Snow Lake, looking back at the Biafo Glacier.

The Snow Lake, looking North West

The Ogre from our camp at the Snow Lake.

Sunrise from our camp at the Snow Lake.

Day 7, we departed our camp at Snow Lake to cross the Hispar Pass. We started very early to take advantage of the frozen snow. The area of the Hispar Pass has a lot of hidden crevasses.

Approaching the Hispar Pass on the horizon, Skam La Pass and to the right (around the buttress) is the Biafo Glacier.

Climbing to Hispar Pass.

Hispar Pass 5,151m The pass is actually a large and levelled snow field like a large plateau. We were planning to camp there but due to high winds we decided to camp further down.

The Hispar Pass 5,151m

The Hispar Pass

Looking back at the Snow Lake

Snow Lake

Snow Lake

Snow Lake

Approaching to the top of the Hispar Pass 5,151m

Skam La Pass on the left in the clouds. Below it, the Snow Lake.

At the top of Hispar Pass

Hispar Pass 5,151m

Looking back from Hispar Pass to the Snow Lake

The Top of Hispar Pass 5,151m

Looking down the Hispar Glacier from the top of Hispar Pass. We camped by the green lakes below. The campsite was near Khani Basa Glacier at 4,530m. As we approached the camp, the snow got progressively softer making walking difficult.

The surface snow melt on the Hispar Glacier which is 49km long. Our campsite near the Khani Basa Glacier at 4,530m.

Our camp at 4,530m

Day Hispar Glacier, the night of Day 7 at 4,530m

Hispar Pass from Hispar Glacier side and our camp right below the Hispar Pass on Day 7 at 4,530m.

Camp on Day 7

Our porters descending from Hispr Pass

Day 8, we hiked for 5 hours from the Khani Basa camp to Shikambarish Camp at 4,170m. We traversed the Jutmo Glacier and finished the day in a downpour. On the way, we had to traverse a hill/moraine of liquid mud that made our progress slow and tedious.

En route to Shikambarish camp on Day 8.

Hispar Pass on the left and the Hispar Glacier on Day 9

Yutmaru Glacier

Yutmaru Glacier and Yutmaru Sar 7290m in the centre.

Looking down the Hispar Glacier from our camp near Dachigan at 4,000m on Day 9

Crossing the Pumari Chish Glacier en route to the camp near Dachigan at 4,000.

Day 9 en route to Dachigan camp.

On the Hispar Glacier.

On the Hispar Glacier

The view from Dachigan camp on Day 9 at 4,000.

The view across the Hispar Glacier from Dachigan.

Steep climb after crossing the Pumari Chish Glacier.

Day 9, Dachigan. From Dachigan, we walked to Hispar Village on Day 10 for 6 hours. We camped at the Huru Village. We had to walk from Hispar to Huru for some distance. The walk was longer than normal due to landslides. On this trek, we walked the total distance of 132km and ascended only 2,750m in total.

From Huru, we took a jeep to Karimabad we were hang our for a day in the Hunza Baltit Inn. On July 7 we drove to Chilas via Gilgit. We were now back on the Karakoram Highway. On July 8, there were serious terrorist attacks in London. This necessitated an armed escort for our group from Abbottabad to Islamabad. We did not know what was going on. The police with guns showed up and wisked us through all the intersections and red lights along the way. Only after arriving at the hotel in Islamabad we found out what had happened in London. We stayed in Islamabad on July 9th and flew home on July 10th.

Ellesmere Island - Lake Hazen to Tanquary Fjord in the Canadian High Arctic

Quttinirpaaq National Park is a Canadian national park. Located on the northeastern corner of Ellesmere Island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, the most northerly extent of Canada, it is the second most northerly park on Earth after Northeast Greenland National Park. In Inuktitut, Quttinirpaaq means "top of the world". In order to get there, one must fly to Resolute and from there, one must take a Twin Otter plane on a four hour flight further north. The flight requires a refueling stop at the Eureka Military Base half way up the Ellesmere Island. The plane is equipped with large balloon tyres to enable it to land on a grassy tundra. During the summer, there is 24 hour daylight. The starting point of the trek is Lake Hazen, located at the latitude of 81 degrees north and approximately 1,000km south of the North Pole. Lake Hazen is located to the north of the Earth's magnetic pole making compass navigation impossible.

The location of Ellesmere Island.

The 100km long trekking route from Lake Hazen (in the middle of the map) to Tanquary Fjord (on the lower left part of the map) traverses the Quttinirpaaq National Park.

Lake Hazen

Lake Hazen

Lake Hazen

Lake Hazen

Lake Hazen

Lake Hazen

The Henrietta Nesmith Glacier

Henrietta Nesmith Glacier

Turnstone Glacier

Turnstone Glacier

Turnstone Glacier

Adams Glacier

Adams Glacier

Tanquary Fjord and mummified Muskoxen

Adams Glacier

Adams Glacier

Lewis Lake

Garfield Range

Garfield Range

Lewis Lake

Lewis Lake

Camping by Adams Glacier

Lewis River, we were aiming for the hills on the left on the horizon

Part of the Ad Astra Icecap

Lewis LAke

Arctic wolf

Parks Canada station at Tanquary Fjord

Tanquary Fjord

Old supplies in the Parks Canada Station at Tanquary Fjord

An antique Bombardier snow machine at the Parks Canada camp